Authentication

Avoiding Authentication System Lock-In

By Cameron Pavey, Dan Moore

Years ago your team decided to use a third-party authentication system to avoid the time and cost of building one in-house. But now a better option has hit the market and you’re wanting to make the switch. Except, hold on, your old system is so deeply ingrained into your organization that you’re practically locked-in to your current vendor.

Authentication system lock-in is a big problem. While there are multiple benefits to using a third-party auth system, such as robust security maintained and improved by a team of engineers, out-of-the-box auth UI, and handy features like analytics and logging, there are just as many downsides.

There is always the monetary cost, which for services like this is typically ongoing rather than a one-off. Having less direct control means you don’t have to maintain and monitor it; however, there isn’t much you can do if there is an outage or performance issue. Finally, the aforementioned vendor lock-in problem can leave you feeling trapped and unable to move away from your provider if you haven’t taken steps to mitigate this risk.

Well we can’t solve all of those problems, but we can at least show you how to mitigate the risk of vendor lock-in. In this article, we cover a few different tips and strategies you can apply when it comes to authentication systems like Auth0, Okta, or FusionAuth.

Look for Open Standards#

As with any project, planning plays an important role. You can avoid nasty surprises down the line by conducting a proper analysis of the options available to you and weighing the pros and cons of each potential vendor. Remember, not all auth systems are made equal, and some are bound to be stickier than others, which is not something you want if you are looking to minimize vendor lock-in.

Be sure to focus on standards-based offerings. If your goal is to avoid vendor lock-in, novel or proprietary solutions are not generally going to be suitable for you. In the case of auth providers, look for support for open identity standards like OpenID Connect, OAuth, SAML, etc.

While open standards aren’t a silver bullet, you will find it easier to migrate to another vendor in the future if your system relies on open standards also supported by other vendors.

Consider Portability#

Another primary concern with any third-party service is portability. If you need to leave in the future, how difficult will it be to get your data out and migrate it to the new provider?

Auth services store varying amounts of data depending on how you have them configured. Still, most of them will maintain at minimum a list of all authenticated users and their supported authentication mechanisms (social logins, enterprise logins, email/password, etc.).

In some cases, you have more control over how this data is handled and might even be able to provide a self-managed database for the provider to use for data storage. Having this option is good, as the data stays with you, but it isn’t always an option or viable to do so. At a bare minimum, you want to be able to export your data from one provider if you decide to leave, and ideally have a way to import it elsewhere easily. Some third-party services will provide resources on how to do these migrations, as is the case with FusionAuth, when migrating from Auth0.

If you end up going with a provider who doesn’t offer full-data exports, you may be in trouble down the line. Data like Rules and Roles might need to be manually reconfigured in most cases, or scripted with something like Terraform. User data - including password hashes - will be much more problematic if you cannot get it out of the system when you need it, so be sure to check on this before making a decision.

Limit Your Usage Where You Can#

Regardless of which provider you go with, many of them offer the ability to store extra data in their system. Being able to store things like user properties and roles on their system seems nice at first, but might be more trouble than it’s worth. Generally, it is better to keep details about your user and their relation to your application, in your application. You will doubtlessly have a user model in your system, and this is a better place to store these details (or on related models) because it gives you an extra layer of insulation from the auth provider.

Even if you might want to filter authorization to an application so that only your employees can access it, this would be an excellent time to use provider-side attributes to flag authorized users. In this scenario, you’d likely have a better time adding authorized users to a group in your enterprise identity system (such as a business Google or Microsoft account) and asserting that property in your auth system. This way, even if you need to move to another provider later, your user attributes will remain intact without needing to be migrated.

Insulate Your Application#

When implementing an authentication system (and various other services provided by third-party vendors, such as storage), there is usually an integration involved. This integration requires writing code in your application to interact with the vendor’s service.

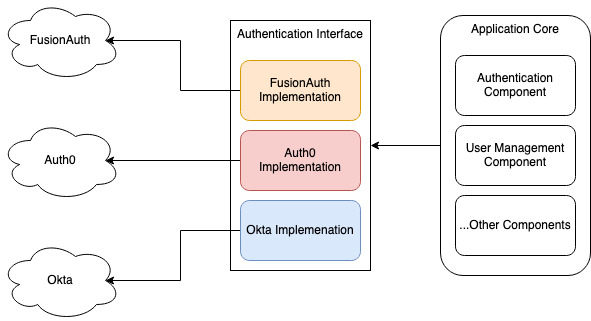

It is usually a good idea to write this code so that the vendor is insulated away from your application code. Often, vendors will provide an SDK for interfacing with their service. By wrapping the usage of this SDK and abstracting it with a more generic interface, we can have greater control over how the vendor ties into our application.

If the vendor uses Open Standards as described above, this makes things easier. We can build an interface that describes how we would ideally like to interact with our authentication service and then implement this interface with a wrapper around the vendor’s SDK. In the future, if things go south and we need to break away from the vendor, we can just re-implement this interface. We’ll write an integration for a new provider, and with any luck (and plenty of testing), things will transition smoothly.

As you can see in this simple diagram, by having your core services rely on a generic abstraction of an authentication system rather than a concrete implementation of one, you can retain the freedom to reimplement the interface. This allows you to switch to whatever provider you like. If you built a concrete dependency on one particular provider instead, you would have lots of refactoring and retesting to do when switching implementations. Naturally, even with a well-abstracted interface, you will still need thorough testing.

It’s crucial to build integration tests around this kind of abstraction. Having integration tests in place to give you confidence in your abstraction and interface is always good, but especially so when there is the possibility of re-implementing the underlying code at some point. As long as the new implementation holds to the interface, you will have a good level of confidence that things are working as expected and that your application will continue to work after a migration.

Have a Backup Plan#

Generally, you don’t implement one solution while actively planning to swap it out in the future. Because of this, it is easy to accidentally put on the proverbial blinders and only focus on what is right in front of you without seeing the bigger picture and the long-term ramifications of certain design decisions.

This can lead to situations where implementations become too specific to the current vendor and are prohibitively expensive to change in the future. “If only we had known we were going to switch providers, we would have done things differently.” Factoring in and budgeting for a plan B or future migration can mitigate such tunnel vision.

This works by identifying an alternative solution - whether it be another provider or building it in-house - and keeping it in mind when designing things and makings decisions. You should work it into your project’s future budget and just accept it as potentially necessary.

Sure, you hope never to invoke plan B - and the cost it would entail. Still, if you built everything with this eventuality in mind, your decision-making process is likely to be more deliberative and ultimately less tightly coupled to your chosen vendor. Factoring in the potential resource cost will also help you avoid ending up in a position where you must migrate but don’t have the budget.

This is a similar principle to the test-first mindset. If you write your code with testing as a foremost concern, the output will likely be different - and more testable by nature - than if you conducted testing as an afterthought. Making architectural decisions while mindfully being aware of possible future migrations can lead to more robust system design and easier migrations in the future.

Technical Planning For A Migration#

There are certain technical issues you should consider as well. Planning upfront for these will help you avoid pain if you do need to invoke plan B or migrate away from an authentication system.

Password Hashes#

While password hashes are briefly mentioned above, understanding how they might lock you in is critical for future flexibility. Having access to your hashes allows you to perform a smooth migration of users who log in with those credentials. A password hash is always one way, so if you cannot get acquire them, you are left with the following unsavory options:

- never migrating

- resetting all your users’ passwords

- performing a drip migration

There are two password hashing concerns to be aware of.

First, what is the hashing algorithm used for your passwords?

Your authentication system documentation should specify this. It’s best if this is an industry-standard hash such as

Second, can you get access to the password hashes?

It’s not typical to have regular or API access to hashes, as they are highly sensitive. Sometimes you can get a database export of your authentication system including the hashes. If you are using a SaaS authentication system, you may need to open a support ticket to get the hashes. Verify such an export is available by consulting the authentication system documentation. Don’t forget to allow for the time needed to obtain the export when actually planning a migration.

Hostnames#

Control the hostname of your authentication system and make sure it is under a domain name your organization owns. Having this under your control makes any future migration much easier.

Your users won’t need to change the URL they visit to authenticate. While most people use links from within your app to authenticate, some people bookmark login pages when using a browser.

If you are integrating with other identity providers, which is common in the business to business to employee (B2B2E) SaaS use case, running an authentication system at a hostname you control is critical.

Common authentication standards which allow for single sign-on, such as SAML and OIDC, embed hostnames and paths into configuration. The terminology used varies, but the functionality is the same: the identity provider needs to send a properly authenticated user to a known location, and this list is often set up when the integration is set up, often by employees with high levels of access, such as IT admins. Such integration allows employees easy, secure access to your application.

If you enable SAML or OIDC single sign-on integration with your application, make sure you use a hostname under your control. Otherwise, during a migration you may need to coordinate configuration changes across many customers, run multiple systems so you can migrate customers on their timeline, or relax security checks (when possible).

Paths can change between authentication systems as well. If you control the hostname, you can configure a proxy to rewrite paths, which will make a migration easier as well.

Wrapping Up#

There will always be the potential for issues when switching out something as central to your application as authentication, no matter how much you plan and prepare in advance. This risk can be reduced or eliminated by following practices like those described above to protect your application from the uncertainty inherent to third-party integrations. The value that using a service like this brings is not to be understated, as long as you understand the risks and take appropriate measures to minimize them.