Authentication

The Security Implications Of Passwordless Authentication

By Niel Thiart

With the rise of passkeys accessed by biometrics in laptops and phones, passwordless authentication seems within reach. Here’s what you need to consider.

Tech luminaries have been prophesying the imminent death of the password for the past 20 years. Or so I’ve been led to believe. If you Google the phrase “the password is dead”, you’ll find an endless list of articles pointing to the 2004 RSA Conference, where Bill Gates allegedly predicted the password’s sudden demise. A death that, as Mark Twain would have put it, has been greatly exaggerated.

The most damning thing Bill Gates said at the conference, was that passwords “just don’t meet the challenge for anything you really want to secure”. The headlines at the time, still repeated today, included variations of “Gates predicts death of the password”. Tech journalism is not above sensationalism.

Hey, look, I know it’s fun to point out the founder of Microsoft’s bad predictions about security, but saying passwords are not secure enough was as true in 2004 as it is now. As far as I can tell, Gates never even said anything about the death of the password, nor should we try to make that claim today. Passwords are as old as language itself, and they’ll probably outlive all of today’s fancy new authentication methods.

That doesn’t mean we can’t acknowledge how deeply flawed the password is. Its faults are too numerous to discuss in detail, but here are the highlights. Most users enter the same password for all of their accounts. Many online services store users’ passwords as plain text, or they use weak hashing algorithms (or Base64!). Passwords get emailed around, stuck on computer monitors, read aloud over the phone to anyone who asks, and entered into any form that pops up when we click on links in emails. According to Have I Been Pwned?, the password 12345 has been seen 2,591,854 times in data breaches, and is not even the most popular one.

Password rules have become so comically complex that developers make Kafkaesque games about choosing passwords, and there is an all-too-familiar feeling called password fatigue that has a dedicated Wikipedia page!

No wonder we wish that for once someone would be right about predicting the death of the password. But completely replacing passwords is not the point. The industry is working on ways to decrease our reliance on passwords by just enough to prevent the worst of the problems listed above.

The solution lies in striking a balance between user convenience and security. Solving this equation has been the focus of the FIDO Alliance since February 2013, but for years it may have looked like their work has amounted to little more than multi-factor authentication for YubiKey-wielding technologists and security specialists.

There is hope, though. Ever since Apple’s austere announcement of passkeys at WWDC 2022, there has been a sudden flurry of activity around the idea of passwordless authentication for consumers.

The casual way in which Apple, Google, and Microsoft present this technology to end users has caused some concern among IT and security professionals. Years and years of repeatedly resetting users’ passwords while begging them to use stronger passwords, only to have the passwords leaked or guessed, have instilled a healthy skepticism of anything left completely in the user’s hands.

Let’s unpack the nebulous concept of passwordless authentication.

Why Now: The Rise Of Passkeys

In 2013, Apple announced Touch ID for the iPhone 5s. Users could now unlock their phones by pressing a finger against a tiny sensor on the front of the phone. In subsequent models, Apple expanded Touch ID capabilities to authenticate App Store purchases and make electronic payments. Apple later added Face ID, which allowed users to do anything Touch ID could do, but by just looking at their phone’s screen.

Other device manufacturers released similar features, to the point where almost all new mobile devices released today feature some form of biometric authentication for passkey authorization. Initially, some users raised concerns about sharing biometric data with service providers, and the potential for abuse by powerful state actors. At least in the case of Apple, face and fingerprint data never leave the user’s device unencrypted, and are isolated in a secure enclave while saved on the device.

Biometric authentication proves with a great degree of certainty that the user is present, and these methods are difficult to spoof. Most importantly, unlocking your phone by looking at a screen is as low friction as it gets. This convenience is a critical part of passwordless authentication’s success.

How Authentication Experience Shapes Habits

When Touch ID first appeared, the little resistance uttered was not just about the privacy and security aspects. Writing in New York Magazine shortly after the Touch ID announcement, Kevin Roose pointed out how historical data showed that “ordinary users, it seems, would rather type in a passcode than fiddle with a fingerprint scanner”. This was based on the past, and may very well have been right at the time.

The iPhone Touch ID worked well enough that users took the path of least resistance and embraced unlocking their phone with a fingerprint. Besides, there was still the fallback, and we weren’t giving up any of our previous authentication methods in the process.

This transition was a catalyst for the passwordless authentication progress we’re seeing today, but can also be framed as a parallel process in terms of the implications. We’ll get to this shortly.

Passwordless Authentication Improves User Experience

The relationship between user experience and passwordless authentication goes both ways. Users expect the apps and devices they interact with to provide the least cumbersome experience possible.

We can safely assume that, all else being equal, users would favor the app with passwordless login over an otherwise identical app with strict password requirements and validation emails for password changes. Currently, this is speculation, but the signs are there: The economics of offering a seamless user experience will drive services to adopt and even encourage passwordless authentication.

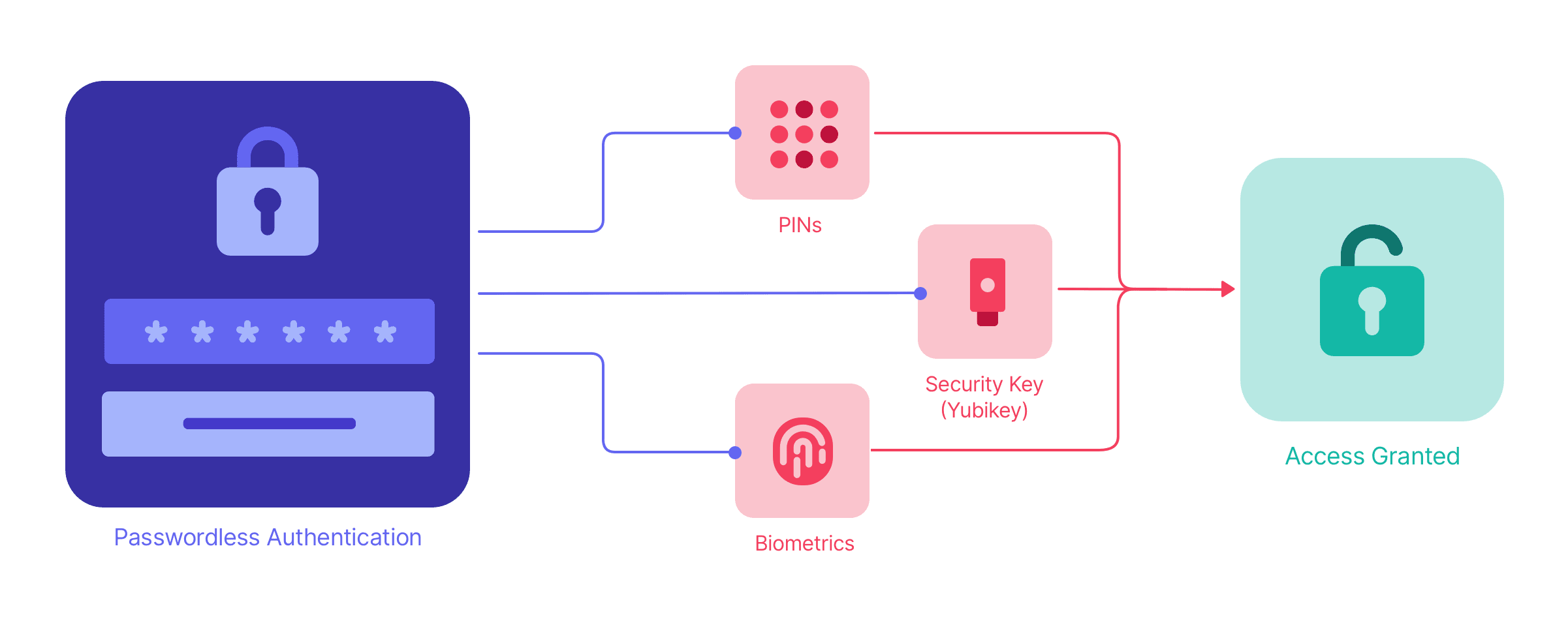

Physical Security Keys And Passwordless Authentication

Physical security keys represent another step toward a passwordless future. These small, portable devices, such as those provided by Yubico or Google’s Titan Security Key, offer a form of two-factor authentication. Since the first factor is usually still a password, this combination can’t be called passwordless in the sense we’re aiming for, but the action of authenticating with a YubiKey is completely passwordless.

In other words, one of the factors in this combination has always been passwordless. The technology that enables passwordless authentication on a YubiKey is similar to that used in passkeys. Like passkeys, security keys are easy to use, with most requiring just a simple tap to authenticate the owner. They communicate with your system using either USB, NFC, or Bluetooth, depending on the specific product and device.

YubiKeys also play a more direct role in the transition to passwordless authentication, as they can, starting with the YubiKey 5 series, create and store passkeys. There is a catch, though.

Passkeys come in two different shapes, and the most user-friendly of the two is a resident key – more on this below. Resident keys take up valuable space on what Yubico calls the YubiKey’s secure element. Space in the secure element is scarce, which means current YubiKey models only have space for 25 resident keys.

Furthermore, these passkeys are hardware-bound. Once a YubiKey generates a passkey, the FIDO2 credentials can’t be deleted or copied – the space is sacrificed indefinitely.

Resident Keys Vs. Non-Resident Keys

The move towards a passwordless future hinges on the concept of “resident keys”. Essentially, there are two types of keys in this world – resident keys, also sometimes called discoverable keys, and non-resident keys.

The main difference between these two lies in the fact that for non-resident keys, users need to provide their username to start the authentication process, and the server then sends a challenge that matches the stored public key. In the case of resident keys, the user doesn’t have to provide a username. Instead, the key can be identified directly by the server, which makes the whole process smoother and more simplified.

This brings us back to the key benefit of passwordless authentication: convenience. With resident keys, users can simply use their biometrics or the security key to unlock an account, skipping the step of entering a username, thus making the login process faster and more efficient.

However, this process does raise a few questions about hardware restrictions and the capacity to store keys. As discussed earlier, current models of security keys like Yubico’s have a limitation on the number of resident keys they can store. Once maxed out, users would need a second security key for additional accounts. It’s a limitation crucial to keep in mind when considering deploying passwordless authentication, but it shouldn’t impact those who use it for personal accounts or even professionals handling a limited number of prioritized accounts. As technology continues to advance rapidly, it’s likely these storage limitations will expand over time too.

Unfortunately, the decision of whether to use resident versus non-resident keys isn’t up to the user. Web services that offer passwordless authentication will determine the key type used based on whether they require a username to log in.

Mobile phones have ample space for resident keys, so for most users, this limitation would not apply.

How Passwordless Authentication Protects Against Common Cybersecurity Threats

Passwordless authentication offers protection against a wide range of cybersecurity threats. Let’s see how.

Phishing

With passkeys and WebAuthn, users do not have access to their private keys, and an authenticating device will only sign an authentication request if it receives the correct credentials from the server. Combined, these traits significantly decrease the threat of phishing attacks. Because users are no longer entering memorable information, like passwords, attackers can’t trick users into divulging these sensitive details.

Malware

Malware often targets weak points like passwords. Without passwords to exploit, the surface area for possible malware attacks decreases. However, this doesn’t mean that all malware threats are eliminated. Cybercriminals can still exploit other vulnerabilities on a user’s device with malicious software.

Social Engineering

Social engineering attacks rely on tricking humans into revealing secure information like passwords. By eliminating the need for users to remember and enter passwords, passwordless methods such as WebAuthn drastically reduce the risk of successful social engineering attacks.

Data Breaches And Cyberattacks

In a passwordless world, attackers won’t be able to obtain a treasure trove of password data in the event of a data breach. This doesn’t necessarily prevent breaches from occurring, but it significantly reduces the damage. By storing only public keys, and ensuring private keys never leave a user’s device, even if an attacker breaches a server, they won’t gain the ability to impersonate users.

Brute Force Password Cracking

As the name implies, brute force attacks involve adversaries trying multiple combinations until they crack a password. These types of attacks become irrelevant with passwordless authentication. There simply isn’t a password to crack. Attackers cannot guess a private key with brute force due to its complexity and length.

Buyer Beware: None Of These Protections Apply Today

Notice that in each of the threats listed above, the protection relies on a situation where there is absolutely no password, or where the user does not have any way to access the password if there is one. All services offering passwordless login today employ passwordless methods as additional login methods alongside traditional passwords.

The false sense of security offered by a service that offers WebAuthn in addition to passwords could potentially negate the benefits of WebAuthn and passkeys.

In a world where passwordless authentication is not truly passwordless, we run the risk of users further devaluing the importance of good password hygiene. Telling someone they never have to use their password to log in again could very well be interpreted as: your password is no longer important sensitive information.

This warning becomes irrelevant if a service deletes the user’s password when the user first sets up a passkey, but I have yet to see an example of this in practice.

The Downsides of Going Passwordless

While passwordless authentication undeniably offers a range of benefits, it also comes with its share of drawbacks and criticisms that warrant discussion.

Irrevocable Biometric Data

The first concern lies in the nature of biometric access. Once compromised, biometric data such as fingerprint scans and facial recognition patterns cannot be changed as easily (if at all) as a traditional password. The standards proposed today encourage authenticators to store biometric data in a secure enclave or trusted platform module (TPM), where it can’t be accessed or copied.

Device Dependence

Another potential pitfall of passwordless authentication lurks in its dependency on local devices. If a user loses their device or it gets stolen, hacked, or damaged, the user could be locked out of their accounts. Physical security keys, though effective, also suffer from similar problems where loss or damage could result in inaccessible accounts.

This shortcoming warrants the addition of fallback authentication methods, which could weaken a user or server’s security posture.

Storage Limits For Resident Keys

Furthermore, the limitations of security keys – like storage space constraints for resident keys – are an issue. This is particularly relevant for users who frequently switch between devices or use multiple services; mobile phones may not have this limitation, but the lack of universal rules leaves the matter uncertain.

False Sense Of Security

Finally, the transition to passwordless authentication will be complex, expensive, and slow. We can assume that services will offer password authentication alongside passwordless authentication for years to come. During this time, traditional passwords will remain a weak link.

In essence, these potential drawbacks underscore the importance of careful consideration before deciding to transition to passwordless authentication. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution, and like all security measures, passwordless authentication options require regular reviews and adjustments.

Scenarios Where Passwordless Authentication Is Not Ideal

While the convenience of passwordless authentication methods cannot be overstated, there are scenarios where these methods might not be the ideal solution. One of the quintessential examples involves users with limited access to up-to-date technology. For individuals using dated hardware or software, compatibility issues with newer web standards like WebAuthn can pose a significant challenge. In such cases, traditional password-based authentication remains the most accessible and reliable method.

Emerging markets, where sophisticated devices with biometric capabilities are less prevalent, often face similar challenges. Even in areas where modern solutions like biometric authentication are available, issues like inconsistent internet connectivity can hamper the smooth functioning of passwordless authentication mechanisms.

There are also scenarios in which multiple users share a single device. In households or workplaces where device sharing is common, biometric authentication can create an obstacle. Passwords, on the contrary, allow for easy account transition and sharing, making them a more convenient option in such settings.

These situations might not apply to companies serving select markets, or considering passwordless authentication for internal systems. These scenarios do, however, increase the likelihood that many public services will offer hybrid password and passwordless authentication systems for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion: Passwordless Security Isn’t As Passwordless As It Seems

Passwordless authentication presents an enticing future. It promises an improved user experience, enhanced protection against various cybersecurity threats, and a shift away from the dearly flawed password system that dominates today.

But it’s not a panacea. Challenges related to biometric data, device dependence, storage limitations, and a potential disconnect with emerging markets remind us that it cannot entirely replace traditional password methods yet. It simply represents another tool in a growing security toolbox, and like its counterparts, needs careful implementation and ongoing adjustment.

While we are still a considerable distance away from passwords being completely “dead”, we are certainly making promising strides toward relying less on passwords. Let’s proceed with the cautious optimism that suits any emerging technology.

Until the password is in the grave, keep choosing strong passwords, think twice before entering your password after clicking a link, and make sure you set up multi-factor authentication on any service that allows it. Remind others that a passwordless world is an ideal but by no means a reality.