OAuth scopes allow your users to grant permission to data held by you to third-party applications. As APIs become more common, and especially with the growth of agentic AI, proper security and consents around data access become more and more critical.

By the end of this post, you’ll know what scopes are, how and why you’d use them, and how to design them to ensure adoption and maintainability.

Third-party applications where scopes make sense include:

- those offering custom functionality, like an analytics engine built on top of your fintech APIs

- AI and LLM tools using the model context protocol to interact with APIs

- apps providing a different interface to improve the user experience

We’ll talk more about the scenarios where scopes make sense and design considerations. But first, let’s talk about what scopes are.

What Are Scopes

Scopes are fundamentally a way to give users more control over the data applications can access by creating groups of permissions that the user can allow or deny to an application.

Scope Scenarios

Normally, the types of data accessed by an application talking to a service or API are determined by the developer of each of these. Scopes introduce a mechanism for the end user to allow or deny data access by an application.

Because scopes are used by an application to request permissions for data, scopes are only useful when:

- the API or service holds data about the end user, such as bank data or offers functionality related to the user, such as sending an email on their behalf

- the application requesting the data or functionality is not owned by the same entity as the API or service

If the data the application needs to access does not relate to the end user, there’s no sense in using scopes since their defining feature is that they give the user a chance to offer or revoke consent. Use another form of authorization instead.

If the application is owned by the same organization as the API or service, then the user has implicitly or explicitly given permission to their data in order to get it into the API or service. In this case, scopes have minimal value. They could ratchet down permissions, but there are other ways of achieving this without user consent.

Now that you’ve learned about scopes in the abstract, let’s get down to nuts and bolts.

Scopes Fundamentals

Scopes are defined as a set of space separated strings in a request, with each string representing a user-understandable set of permissions.

Since a bank has a different set of permissions than an email service, scopes are specific to the business offering the data or functionality. The organization running the platform holding the data and the server the user logs in to, the Authorization Server to use the jargon of the OAuth spec, defines the meaning of each scope.

Scopes are not further defined in the OAuth specification, though there are standard scopes defined in some other standards (such as OIDC).

The underlying meaning of a scope is tied to the implementation. That means when you are building a system with scopes, you need to design them to meet your needs. That’s the point of this post.

Next, let’s take a deeper look at what the standards say about scopes.

Enhance your platform’s security with well-designed OAuth scopes. Schedule a demo to see FusionAuth’s capabilities.

What Do the Standards Say

There are a few RFCs which discuss OAuth scopes; we’ll look at 6749 and the OAuth 2.1 draft below. Before we do that, here’s a primer to help translate RFC jargon into terms developers use:

- A token: a string or value which proves the holder has access

- A claim: a piece of information, typically about a user or software program

- Grant: a standardized flow a user or other entity can follow; when successful, the entity ends up with a token

- Resource owner: the end user, usually a person

- Client: an application which needs access to data or functionality; it is seeking a token

- Authorization server: where the user logs in; responsible for minting tokens which prove the client is authorized

- Resource server: the API or service; accepts tokens and returns data or functionality

Now that that translation is done, let’s see what standards have to say about scopes.

Scopes are defined in the OAuth 2 RFC (6759). Here’s most of the RFC section (I edited it a bit to make it easier to read).

The authorization and token endpoints allow the client to specify the scope of the access request using the “scope” request parameter. In turn, the authorization server uses the “scope” response parameter to inform the client of the scope of the access token issued.

The value of the scope parameter is expressed as a list of space- delimited, case-sensitive strings. The strings are defined by the authorization server. If the value contains multiple space-delimited strings, their order does not matter, and each string adds an additional access range to the requested scope.

The authorization server MAY fully or partially ignore the scope requested by the client, based on the authorization server policy or the resource owner’s instructions. If the issued access token scope is different from the one requested by the client, the authorization server MUST include the “scope” response parameter to inform the client of the actual scope granted.

If the client omits the scope parameter when requesting authorization, the authorization server MUST either process the request using a pre-defined default value or fail the request indicating an invalid scope. The authorization server SHOULD document its scope requirements and default value (if defined).

Scopes are also defined in more detail in the OAuth 2.1 draft. This is currently a draft but is worth reading because it updates the OAuth2 RFCs based on a decade plus of experience. The key aspects of scopes in the standards documents are:

- scope values are strings

- the scope URL parameter contains scope values separated by spaces; there’s no internal structure

- scopes are defined by the authorization server

- scopes are requested by a client, but they can be denied by

- the authorization server based on its policies

- decisions of the resource owner

- scopes are associated with an access token issued by the authorization server

- the resource server is responsible for enforcing limitations due to scopes

Per the standards, all the actors in an OAuth grant affect scopes:

- the client asks for the scopes it needs

- the authorization server defines the scopes and may have a policy for what scopes are allowed

- the resource owner can instruct the authorization server to ignore a scope request

- the resource server enforces the limitations of scopes

Great, enough with the RFC jargon. No more authorization servers or resource owners for the rest of this post. Promise!

Let’s take a look at how a request with scopes actually happens.

The OAuth Flow With Scopes

Here’s a sequence diagram illustrating the Authorization Code grant for a scoped access token, and subsequent API requests.

sequenceDiagram

participant User as Logged In User/Browser

participant App as Client App

participant FusionAuth

participant APIs

User ->> App : Requests Login Page

App ->> User : Redirects To FusionAuth Authorize URL With Needed Scopes

User ->> FusionAuth : Requests Login Page

FusionAuth ->> User : Returns Login Page

User ->> FusionAuth : Authenticates

FusionAuth ->> FusionAuth : Validates Credentials

FusionAuth ->> User : Displays Consent Page

User ->> FusionAuth : Accepts Consents

FusionAuth ->> User : Returns Redirect To Application

User ->> App : Requests Redirect URL

App ->> FusionAuth : Requests Tokens

FusionAuth ->> App : Sends Tokens

App ->> App : Stores Tokens

App ->> APIs : Requests Data Using Access Token

APIs ->> APIs : Validates Access Token Including Scopes

APIs ->> App : Returns Data

App ->> App : Stores Data

An example request flow with OAuth scopes.

It’s similar to an Authorization Code grant with no scopes requested, except with the following differences:

- a

scopeparameter is included in the authorization URL kicking off the login - there’s a consent screen displayed to the user

- the

scopevalue is included in the access token (which may or may not exactly match the scope parameter) - the API validation must check the

scopeclaim

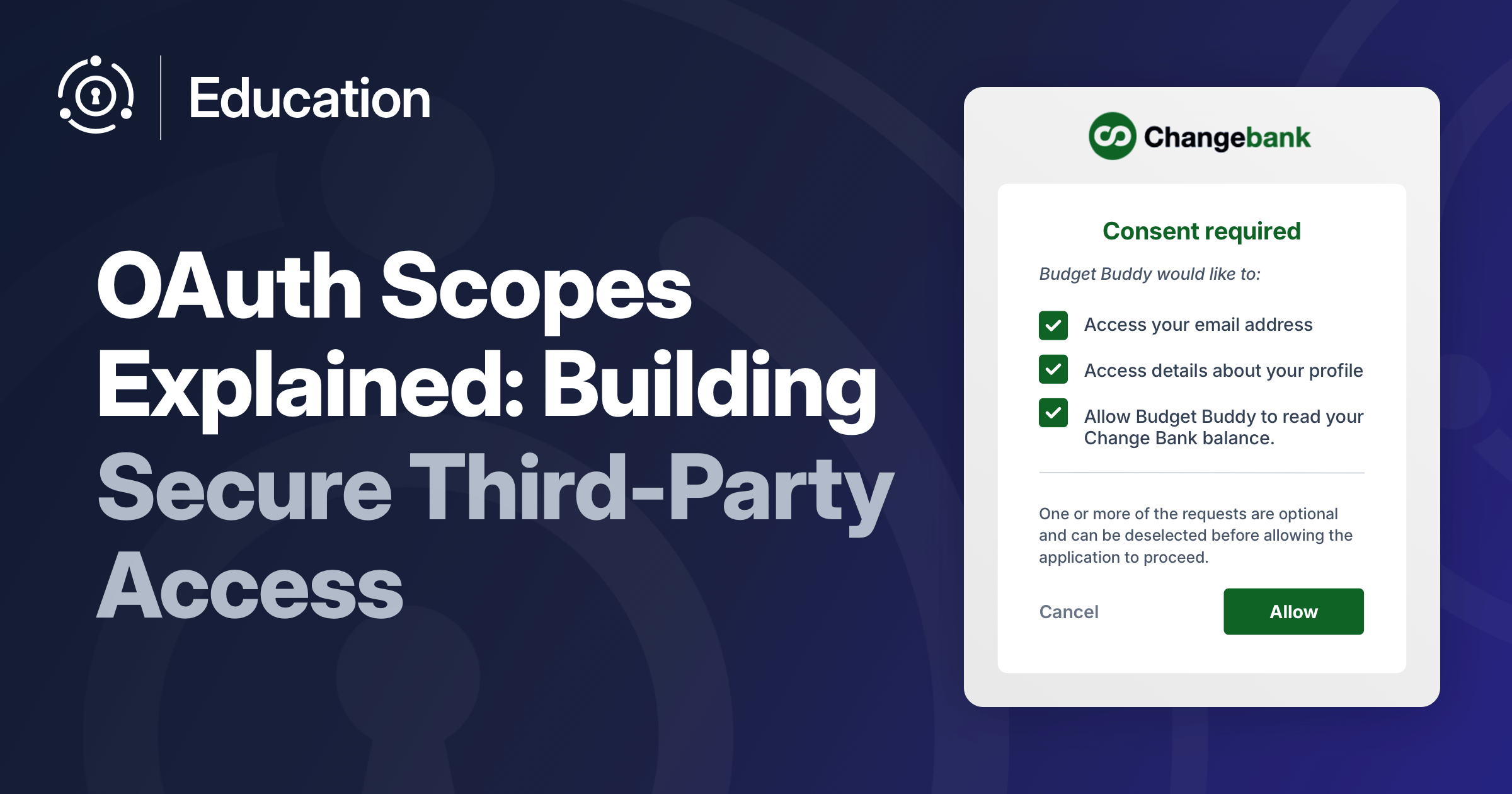

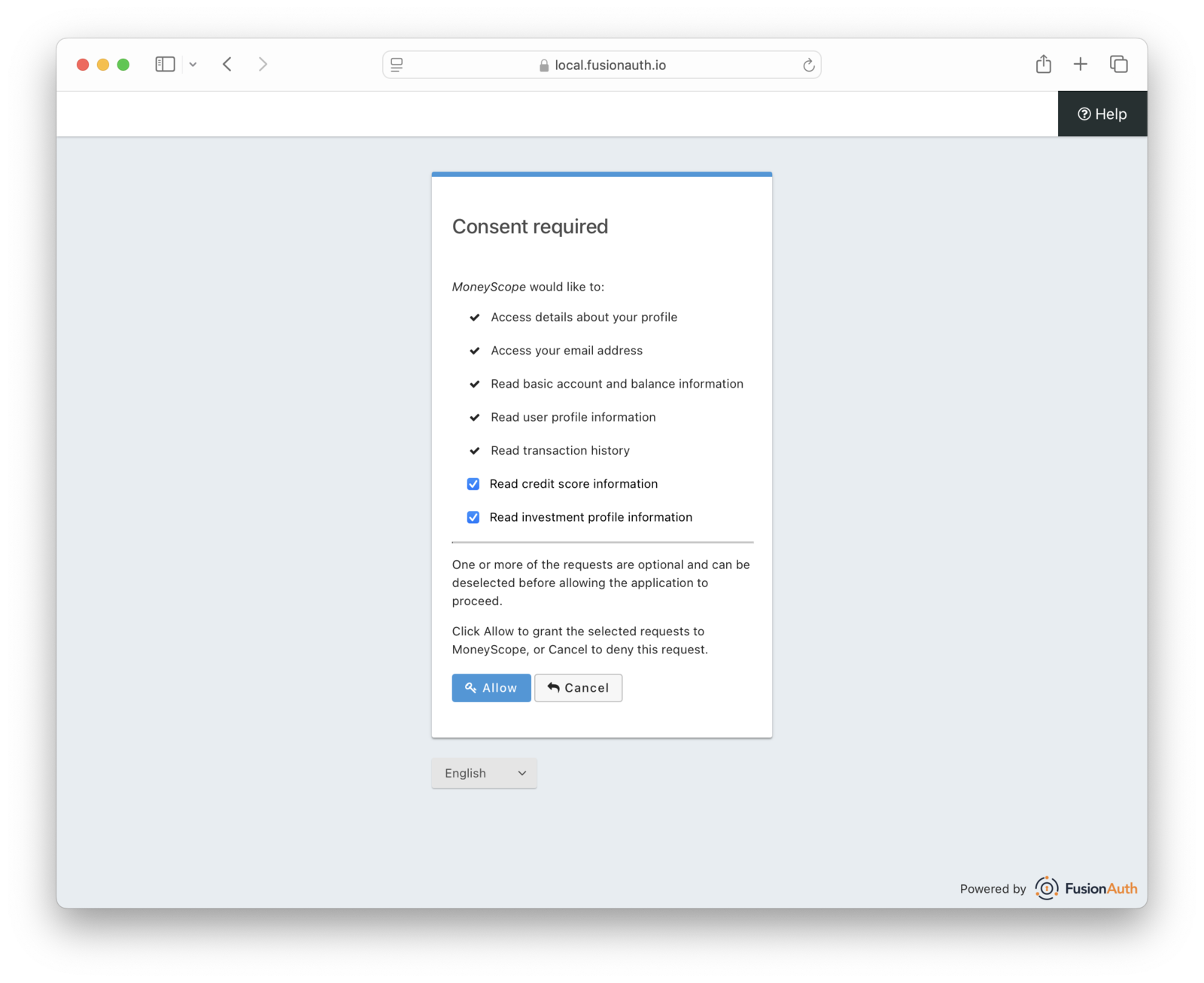

Here’s an example of a consents page that a user might see:

Scopes are related to permissions, but also to other common authorization concepts like roles. Let’s look at how scopes are different from roles.

Scopes vs Roles

The table below outlines the differences between scopes and roles in a role-based access control (RBAC) system.

| RBAC Roles | Scopes | |

|---|---|---|

| Applies to | Users or groups | Tokens |

| Who picks them | Admins or business rules | 3rd party app developers constructing the authorization URL |

| How are they accepted by the end user | By logging in | By explicitly accepting |

| Lifetime | Indefinite until removed | Token lifetime with optional refreshes |

| Access enforced by | Depends on application architecture | The called API or service |

| Visibility to end user | Varies, usually hidden and internal to application | Visible via consents |

As mentioned above, scopes are a good fit when:

- there is a third party that needs to access data or functionality on behalf of an end user

- you, as the platform hosting the user’s data, need or want to offer the user control over what the third party can access on their behalf

If these are not true, it’s better to stick with roles or another form of authorization.

Designing Scopes

To design scopes for your application, you should:

- Talk to external developers about what they want to build on top of your platform. This allows you to check that your API groupings make sense.

- Catalog the APIs you want to expose to third-party developers. A smaller set is better to start with, but ensure enough functionality to entice third-party developers to use the APIs.

- Group functionality. Talk to internal developers about this as they’ll have a sense in how the APIs are used.

- Discuss the implications with your security team, especially if these APIs have not been publicly available before.

- Check with external developers to make sure your API groupings make sense.

You also need to decide what the actual scope values are. These are the strings which developers will add to the authorization URL to request the permissions from the end user. Consider multiple priorities which will be in tension, including:

- end user comprehensibility

- short, understandable names

- business needs

- appropriate granularity; not too narrow or sprawling

- future-proofing; you want them to make sense both now and in the context of future functionality

- implementation simplicity, particularly within the APIs and services that are receiving the scoped access token

Whatever you choose, scopes are long lived once released and incorporated into third-party applications. Beta test with a known set of external and internal developers to test assumptions about the right definitions.

It’s also better to start with a smaller set of scopes and add more later; it is easier to give than to take away.

Below is a list of scopes for a fake fintech company, Changebank. Changebank is building scope enabled APIs to encourage an ecosystem of developers and applications built on their APIs. Not all Changebank functionality is present in their public APIs. Not every developer can access every scope.

accounts.read: Basic account information and balancesprofile.read: User profile and contact informationtransactions.read: Transaction history and detailstransfers.write: Initiate money transfers between accountspayments.write: Make bill paymentsinvestments.read: Investment portfolio informationinvestments.write: Execute investment tradescreditScore.read: Access credit score information

Each of these permission groupings are clear in intent, make sense to the end user, and are something Changebank can expose to a set of developers. There is both a string: creditScore.read, and a description: “Access credit score information”. The string is used in the URL as a parameter. The description is often stored by the server which displays the consent page to make that page more understandable to the end user.

Because scopes require user consent, making sure users understand what they represent is critical. If a user can’t understand the third-party access they are allowing based on the scope name and any additional information on the consent screen, then you have a problem and need to reconsider your scopes.

Also, keep in mind that there are two parties that are involved in picking scopes:

- the third-party developer needs to know which scopes their application needs to provide its functionality

- the user needs to know whether or not the application should be allowed to access the data represented by the scopes

This means that you don’t want your scopes to be too granular, otherwise you’ll run into fatigue from both of these sets of users.

Don’t design overly broad or narrow scopes, otherwise you’ll confuse developers and users, both of whom need to understand them.

The Changebank scope list is good but can be improved. Let’s take a look at how.

Additional Approaches

There are a number of ways to improve the sample Changebank scopes listed above, and some that you might think would be important but can be ignored.

Put Operations In Scopes

Scopes are often tied to resources and operations.

While resources are business specific (Zendesk has tickets, Slack has messages), operations are more general. A common approach is to use read and write suffixes or prefixes for each type of operation. read lets you read resource data and write lets you create, update and delete it.

Breaking operations apart in a manner similar to CRUD, with scopes for update and delete, is overly complex and too fine-grained. Does an end user really understand the difference between creating a payment and updating one? And in what context would an application need to be able to do one but not the other?

To leverage operations in our list, we should add read and write operations for each of the objects above, which gives us:

accounts.read: Basic account information and balancesaccounts.write: Update basic account information and balancesprofile.read: User profile and contact informationprofile.write: Update user profile and contact informationtransactions.read: Transaction history and detailstransactions.write: Update transaction history and detailstransfers.read: Read money transfers between accountstransfers.write: Initiate money transfers between accountspayments.read: Read bill payment datapayments.write: Make bill paymentsinvestments.read: Investment portfolio informationinvestments.write: Execute investment tradescreditScore.read: Access credit score informationcreditScore.write: Update credit score information

Some of these don’t make much sense or would not be exposed to third parties, such as writing a credit score. That operation may not even be available to internal Changebank applications.

Use suffixes to brainstorm complete sets of operations on resources, but you don’t need to create all of them.

Non-Resource Scopes

Scopes don’t have to be tied explicitly to a resource. If you have APIs that offer functionality not directly related to a resource, such as a way to calculate a credit score, you can create scopes for that functionality.

One example for Changebank would be a creditScore.calculate scope. This could be used by a third-party application that wanted to trigger a recalculation of a user’s credit score.

Namespacing

Google uses full URLs for each of their scopes. According to their documentation, this is useful for namespacing:

… it’s a best practice to assign each scope a unique name, in the form of an URN.

Since URNs are globally unique this distinguishes scopes from multiple teams and organizations. If you examine Google’s scopes, most have the same prefix: https://www.googleapis.com/auth/ and are further namespaced in the path after that prefix.

Updating account entries to become URNs results in:

urn:changebank:accounts:read: Basic account information and balancesurn:changebank:accounts:write: Update basic account information and balances

Scopes, other than standard ones, are:

- defined by the organization platform containing data third-party developers want to access

- consumed by APIs created by that same organization

For this reason, namespacing using URNs is usually overkill. Of the external platforms supporting scopes I surveyed, only Google and Microsoft used them.

You are probably not Google or Microsoft.

However, you can also namespace scopes using hierarchy. If you had scopes that were managed by the retail team and others by the commercial team, you can create scopes that reflect that:

retail.accounts.read: Basic account information and balancesretail.accounts.write: Update basic account information and balancescommercial.accounts.read: Basic account information and balancescommercial.accounts.write: Update basic account information and balances

Hierarchy

Since scopes are strings and authorization logic takes place in your APIs and services, you can build in hierarchy. With the Changebank example above, you could add the following scopes that make the account:read scope more granular:

account.profile.read: read the user profile informationaccount.list.read: list accountsaccount.detail.read: read account details

Avoid nesting the hierarchy too deep, such as account.profile.names.firstname.read. I only saw two levels of hierarchy when looking at scopes in the wild. This makes sense because hierarchy can impact scope usage:

- the user might be unsure what the differences is between each of these and why they should grant one and not the other

- the third-party developer might not know which scopes they should request and so will request overbroad permissions

- the API or service offering the data will have increased implementation complexity because the APIs validating the access token and scopes contained in it need to have the mapping of which scopes apply to them

A one to many mapping between scopes and API endpoints is relatively easy to reason about, but hierarchies can be more complex.

Versioning

There are three approaches to versioning:

- don’t version your scope values

- add

v1somewhere in the scope when you first release it - add

v2or other version info when you need to introduce subsequent version

Large providers, such as Google, Slack and Zendesk, do not have version information in their scope strings. You probably don’t need it.

Admin Scopes

Resist superuser scopes such as admin. By not even adding these into your design, you won’t tempt third-party developers into asking users for them.

Being explicit rather than having a catch all scope also forces you to have better design. Finally, avoiding such scopes means you force

Operating Concerns

It’s not enough to just create a nice set of scopes and ensure that they are correctly interpreted in your APIs. Since scopes are primarily used by third-party developers to build on your platform, you need to provide additional support beyond what you might for internal APIs or services without scopes.

Documentation

Clearly document the scopes and how to use them. In the documentation, include:

- a full list of public scopes (this low bar is not cleared by several large API providers, including Microsoft)

- what data or functionality each scope applies to, including sample responses

- any non-functional limits or processes like authentication, rate limiting or pricing

Given the relative unfamiliarity of some developers with OAuth grants, document OAuth basics too. Show them how to add one or more scopes to the authorization URL this this (newlines for clarity only):

${fusionAuthURL}/oauth2/authorize?client_id=${clientId}

&response_type=code

&redirect_uri={redirectURI}

&state=${stateValue}

&code_challenge=${codeChallenge}

&code_challenge_method=S256

&scope=profile%20email%20openid%20offline_access%20accounts.read%20creditScore.read%20investments.read%20profile.read%20transactions.readYou’ll make developers extra happy if you have SDK wrappers or example applications. A scope implementation simply isn’t complete until you document how a third-party developer can integrate with your APIs using them.

Finally, make sure you communicate what third-party developers need to do from a non-technical perspective to get access to your APIs managed by scopes. For example, paying you money, accepting terms of service, or even just verifying an email address for communication purposes. If you aren’t going to grant developers access to APIs, don’t bother building scopes into them.

Telemetry

You should track which scopes are used by which applications, and how often. You should track:

- scope lifecycle: which scopes are used

- security: which applications are using which scopes; audit to make sure this is appropriate

- performance: are requests with certain scopes markedly resource intensive or slow

Of course, it’s a good idea to have these insights into all of your API usage. But they are particularly important to capture when using scopes because the main users of scopes, third-party developers:

- are unlikely to be responsive when asked how they use data access

- may be malicious

- are the reason you are designing and building scope functionality in the first place

Observability is the way to understand how your APIs and scopes are being used.

Lifetime

Because scopes are embedded in third-party software, they live for a long long time. Once someone has a working integration with your platform, they are typically loath to invest effort in updating their solution unless there are significant benefits to them.

Such benefits could be positive, such as access to enhanced functionality or data. Or they can be negative, such as the integration continuing to work after upgrade. Don’t lean too hard on negative “benefits”. When you break an integration, developers get frustrated. When developers are frustrated, they explore alternate solutions.

This is another reason to start with a small set of scopes, because if you have designed the scopes incorrectly, you’ll have fewer to revise and fewer developers will be impacted.

Scope Deprecation

Consider future deprecation when designing your scopes. Things to consider:

- how long will you support a scope that is no longer useful

- what kind of migration support will you provide to developers who use a deprecated scope

- how will you communicate deprecations to your third-party developers

Like many decisions, the precise plan for scope deprecation depends on the size of your platform ecosystem, the length of time the scope has been available, and the severity of possible changes.

You’ll need to be more communicative if you are removing a scope entirely than if you are changing functionality accessed when using it. You’ll need a different communication strategy if you can call the five developers who have built on your platform than if you have thousands of developers who’ve been using a scope for years. In the latter case, it may be impossible to remove the scope!

Consuming Scopes

Let’s talk a bit about what the API or service that gets an access token containing a scope needs to do. APIs must check scopes correctly when responding to a request. Here’s a few example routes from a fictitious Changebank API which check for scopes.

Example Changebank API routes

router.get('/read-balance', hasScope('accounts.read'), function (req, res, next) {

res.json({ balance: 42 });

});

router.post('/make-transfer', hasScope('transfers.write'), function (req, res, next) {

const amount = req.query.newbalance;

// update balance

res.json({ message: "ok"});

});The hasScope method looks like this:

The hasScope logic

function hasScope(scope) {

return (req, res, next) => {

const decodedToken = jose.decodeJwt(req.verifiedToken);

let scopes = []

if (decodedToken.scope) {

// need to check array, not string, to avoid partial matches

scopes = decodedToken.scope.split(" ");

}

if (scopes.includes(scope)) return next();

res.status(403);

res.send({ error: `You do not have permissions to do this.` });

}

}Don’t forget to sanitize user input. Since scopes are part of a URL that is displayed in the browser, a nefarious user or client can modify them before making the authorization request. Make sure your application handles unexpected scopes, whether policy prohibits them for a certain third-party application or whether they are completely unknown.

Write tests around scopes and their access, just as you would with any other security feature.

You must handle scope validation efficiently, since APIs validate scopes on every request. How to do so depends on your API implementation and scope complexity. Handling five scopes is different than handling a hundred scopes with multiple hierarchies. For the former, you can use a simple lookup to see if the scope in the token is associated with the API being called. For the latter, consider a prefix tree or other data structure with known lookup time characteristics.

You can map APIs to scopes with configuration. For example, OpenAPI lets you attach scopes to resources in the configuration file.

paths:

/users:

get:

summary: Get a list of users

security:

- OAuth2: [read] # <------

...

post:

summary: Add a user

security:

- OAuth2: [write] # <------

....If you are using a library or framework to manage your API access, check if it supports scope configuration and validation.

Examples of Scopes In the Wild

Let’s look at some examples of scopes in use today.

Google has over 500 scopes. They use URL values for scopes.

They don’t appear to version scopes in the scope string, but do have different versions of APIs, which may have different scopes. For example, Blogger v3 has two scopes https://www.googleapis.com/auth/blogger and https://www.googleapis.com/auth/blogger.readonly, while Blogger v2 has the https://www.blogger.com/feeds/ scope.

Some services have many scopes, with a few having close to twenty. Others, such as the BigQuery Reservation API, have two: a read scope and a write scope.

Slack

Slack has over 100 scopes and uses both . and : characters to separate scope segments. Slack also distinguishes between scopes that can be used by various types of software such as bots.

You can also see how they deprecate a scope like conversations:history. Interestingly, they announced this deprecation in 2021 but still have not removed the documentation, pointing to the difficulty of removing a scope once it is released.

Zendesk

Zendesk has CRUD oriented scopes, with a focus on resources, such as tickets, users, and organizations. Scopes consist of a resource and/or an operation. Operations can be appended to a resource or standalone, in which case they apply for all resources available to that user.

The Zendesk API also returns an access token even if a requested scope is invalid; they validate the token on the API request and will respond with an error message during that request.

Other Examples

There are many other platforms whose scope design you can review to determine what the best option is for you.

These include:

- Coinbase

- Dropbox

- GitHub example of hierarchical scopes

- LinkedIn - called ‘permissions’

- Microsoft

- Salesforce

- Spotify

- X/Twitter - illustrates rate limits

- Yahoo

Related RFCs

As mentioned above, scopes are a string, though you can add additional structure using delimiters.

The Rich Authorization Requests (RAR) RFC, released in 2023, addresses this limitation by adding a new request parameter: authorization_details. This parameter contains JSON and therefore has a rich structure.

The exact structure of this parameter is undefined, other than a mandatory type field which specifies the type of the request. The RFC also outlines optional fields to handle common authorization needs, such as:

locations: the location or locations of the consuming API (the Changebank APIs in the example above)actions: the action or actions the client application is trying to takedatatypes: the type of data being requested from the APIs

You can add your own fields into the structure of the authorization request parameter JSON as well.

Similar to scopes, the values of all of these actions are dictated by the server issuing the token and consumed by the API server or servers. The authorization_details parameter requires similar design consideration.

RAR is used by some standards such as FAPI2 but is not as widely supported as the scope parameter.

Summing Up

When you are designing scopes, remember:

- they are going to be used by third-party developers, but also need to make sense to end users who will approve or deny them

- if they don’t involve such end user consent, don’t bother

- there is substantial non-technical work required to help a platform using scopes succeed

- if scopes are useful be used for a long long time; plan for that

When designed thoughtfully, scopes help third-party developers request data and functionality and enhance your users’ experiences. Scopes are a standardized part of OAuth and one component of a solid foundation on which to build a platform.

If you’d like to read more about how to use FusionAuth to manage scopes, capture user consent and build out your platform, check out the API Consents Platform use case and this blog post.

Enhance your platform’s security with well-designed OAuth scopes. Schedule a demo to see FusionAuth’s capabilities.