When you are building out APIs for web applications, desktop apps or mobile applications, you must authenticate these requests.

You may say to yourself, “of course, who wouldn’t do that?”. There have been incidents in the last few years where APIs were not protected at large or prominent organizations, including LinkedIn and Parler. There’s an OWASP API top 10 list illustrating industry wide security issues. Authentication is number two on that list.

Let’s take a look at what you need to think about when protecting your APIs. In this post, you’ll learn about where you should verify your API keys and the differences between first-party and third-party APIs.

What Is An API?#

The acronym API stands for “Application Programming Interface” and defines a method for one piece of software to communicate with another. The transport and the message format must be defined and mutually agreed upon, whether the participants are a C program calling into a Fortran numeric processing library, a Python script accessing a Hugging Face LLM model, or a mobile application requesting user data from a web server.

Web APIs vary, but it is common for them to use:

- TLS and HTTP (well, TLS, really) for the transport layer

- JSON and HTTP headers for the message formatting layer

The Players#

Any web API has the following entities:

- a client which is the software program making the request

- an API server which offers protected data or functionality

- an API key which is a unique identifier for the client which can be validated by the API server to authenticate that client

- a central authority which can issue API keys

Throughout this post, we’ll examine a hypothetical todo service run by Pied Piper, the Pied Piper Todo Management System (PPTMS). This service allows users to create, update and delete todos. It’ll have multiple client applications and a web API. For ease of writing, I’ll shorten ‘web API’ to ‘API’.

Users can create and update their own tasks. But users should not be able to access anyone else’s todos.

A client can make a GET request against an API server at https://todo.piedpiper.com/api/todo to retrieve a list of user’s todos. An API key is held by the client and presented to the API server to authenticate the request. The API key needs to be HTTP safe and unique per user, but there are no other constraints.

Here’s an example of a successful API request, where Richard requests information about his todos:

sequenceDiagram actor User as Richard participant API as API Server User ->> API : Get Richard's todos API ->> API : Request validated API ->> User : Richard's todos data

An API request.

But how does the server know which user to get todos for when it receives a request? You need to deny random or malicious users access to precious, precious tasks. Authentication is critical. If the API server knows the caller is Richard, it knows that the requester can read and write Richard’s todos, but not Dinesh’s.

Here’s a failed request, because the user is unauthorized.

sequenceDiagram actor User as Dinesh participant API as API Server User ->> API : Get Richard's todos API ->> API : Request validation attempted, fails API ->> User : Error message

A failed API request.

What API Authentication Needs#

To get access to data from an API, the user or software program needs to provide proof of who/what they are to get access to functionality and/or data. The API authentication mechanism should be:

- secure

- performant

The first requirement of API authentication is to allow only appropriate callers access to data or functionality. This requirement includes how the initial authentication is performed, properly handling unexpected requests, and determining what access is requested and provided.

While you can rely on TLS for web API requests to secure the API key in transit, make sure the API key is secured from unauthorized access on both the client and the API server.

API authentication methods must also be performant. If an API is not accessible due to slow authentication, the API is broken.

API keys, which are high entropy random strings assigned to clients by a central authority, give you both security and performance. Other methods work, such as network access control lists, but API keys are a great solution for internet-enabled web APIs.

API Protection Options#

But to protect the API with keys, you need to verify a presented key is valid. There are three ways to think about API key verification.

- No authentication needed: no verification required

- Centralized verification: where a central authority determines API key validity

- Decentralized verification: where an API server determines API key validity

What does API key validity mean? It is the end result of a process that determines the API key was issued by a known central authority and has not been revoked or expired. When an API key is valid, the requester is properly authenticated.

Protect your APIs like a pro. Schedule a demo to explore how FusionAuth secures API access with fine‑grained control and token management.

Unprotected APIs#

The first option fits when you have a public API that offers identical data or functionality for all users. I once worked on an application that had tremendous scale requirements. It published JSON formatted messages to Amazon S3, which were then ingested by JavaScript running on millions of browsers and displayed data to the end user. This was a read-only API with no authentication. Updating the data this API served happened through a different process where credentials were checked.

Having no authentication simplifies security and performance. It is a good option when no data modification needs to happen, or when there are read-only and write channels, as above.

However, such an approach is the exception rather than the rule.

Far more often, especially when APIs allow clients to update data or offer functionality tied to the user’s identity, you must authenticate and authorize the API request.

Authentication And Authorization#

Typically after you authenticate a request and know who the caller is, you authorize it. This lets the API server know what access the caller has or if access should be denied.

Authentication is “who are you” and authorization is “what can you do”. While they can be treated separately (car keys authorize without authenticating and a business card authenticates without authorizing), they are often considered together.

Authorization can be done in a number of ways, including role-based access control (RBAC), attribute-based access control (ABAC), and relationship-based access control (ReBAC). Authorization decisions are typically embedded in business logic or extracted to a standalone policy decision point (PDP).

An example of authorization is when a request to todos.piedpiper.com/api/todos is received and has a valid API key representing Richard, the system allows read and write access to Richard’s todos. But Dinesh’s todos are not accessed.

The API key doesn’t necessarily contain information about what Richard can and can’t do, but the API server consuming the API key needs to be able to authorize the request after authenticating it somehow. A useful API key authenticates the request and also can be used to determine authorization status.

Finally, APIs are stateless because of the HTTP transport mechanism. Because the todos server supports different clients, browser-specific mechanisms such as cookie-based sessions can’t be used. The API key should be presented to the API server every time.

Centralized vs Decentralized API Key Verification#

Let’s look at the differences between centralized and decentralized API key verification. The Pied Piper Todo Management System allows users to create, update and delete todos and tasks. It’ll have multiple client applications and an API to store data. Users should be able to create and update their own tasks, but not those of others.

We’re not going to deeply discuss how the client gets the API key in this post. You could do this using the OAuth grants or a developer portal issuing static keys, but this section will assume the client obtained a key that needs to be validated.

In this system, there are also other API services. There might be a service for sharing todos or summarizing them using an LLM. Accessing these will also require valid API keys.

These are the important components of the Pied Piper Todo Management System:

- clients which display or add todos

- the todo API server which holds todos data and allows for modification of that data

- API keys which authenticate each client to the todo API server

- the central authority which issues and validates API keys

- other API services, such as a sharing or summarization service

With that context out of the way, let’s look at centralized API key validation.

Centralized API Key Verification#

With centralized API key verification, the central authority is consulted every time there is an API request. On every request, the client presents the API key such as emORxy... to the API server, and the API server in turn presents the API key to the central authority.

The central authority validates the API key using its value and, possibly, contextual information about the request and requested resource.

sequenceDiagram actor User as Richard participant Todos API Server participant Sharing API Server participant LLM Summary API Server participant CA as Central Authority par User to Todos API Server User ->> Todos API Server : Get todos and User to Sharing API Server User ->> Sharing API Server : Share todos and User to LLM Summary API Server User ->> LLM Summary API Server : Summarize todos end par Todos API Server to CA Todos API Server ->> CA : Is key valid? CA ->> CA : Checks key value for Todos API Server CA ->> Todos API Server : Yes and Sharing API Server to CA Sharing API Server ->> CA : Is key valid? CA ->> CA : Checks key value for Sharing API Server CA ->> Sharing API Server : Yes and LLM Summary API Server to CA LLM Summary API Server ->> CA : Is key valid? CA ->> CA : Checks key value for LLM Summary API Server CA ->> LLM Summary API Server : Yes end par Todos API Server to User Todos API Server ->> User : Todos results and Sharing API Server to User Sharing API Server ->> User : Share results and LLM Summary API Server to User LLM Summary API Server ->> User : Summarize results end

API request with central authority validating the key.

What does the central authority look like? It’s named vaguely intentionally, as it could be:

- a database table

- a separate in-memory service

- a standalone server

Conceptually these all offer the same functionality, which is checking if an API key is tied to a user and is valid. Performance and complexity are different for each of these solutions, though. But that’s a benefit of the centralized scenario. You can migrate between implementations without changing the clients or the API server. Having a local solution, such as a database table, makes deployment simple and reasoning about the system relatively easy.

There are other benefits with the centralized approach. Revocation of an API key is trivial. If a client should no longer have access, you update the central authority’s datastore to remove that API key or change its status.

Every request presents an API key to the central authority, so when a user should no longer be able to access their todos, such as when they failed to pay Pied Piper the monthly fee, the central authority removes the API key from its datastore. Subsequent requests fail authentication.

However, with centralized verification, the central authority is a chokepoint. Since each service verifies every request, the central authority needs high availability and performance. As you add more services and more clients, such non-functional requirements increase.

Here’s a diagram showing three parallel requests from three different API servers which all need to have an API key verified.

sequenceDiagram actor User as Richard participant Todos API Server participant Sharing API Server participant LLM Summary API Server participant CA as Central Authority par User to Todos API Server User ->> Todos API Server : Get todos and User to Sharing API Server User ->> Sharing API Server : Share todos and User to LLM Summary API Server User ->> LLM Summary API Server : Summarize todos end par Todos API Server to CA Todos API Server ->> CA : Is key valid? CA ->> CA : Checks key value for Todos API Server CA ->> Todos API Server : Yes and Sharing API Server to CA Sharing API Server ->> CA : Is key valid? CA ->> CA : Checks key value for Sharing API Server CA ->> Sharing API Server : Yes and LLM Summary API Server to CA LLM Summary API Server ->> CA : Is key valid? CA ->> CA : Checks key value for LLM Summary API Server CA ->> LLM Summary API Server : Yes end par Todos API Server to User Todos API Server ->> User : Todos results and Sharing API Server to User Sharing API Server ->> User : Share results and LLM Summary API Server to User LLM Summary API Server ->> User : Summarize results end

API request with central authority validating the key for multiple requests.

Additionally, if you need to integrate with third-party services, you need to figure out how your API key approach maps to their API key protection system. This may require a proxy to translate requests, or additional integration work.

Let’s look at decentralized API key verification, which has a different set of tradeoffs.

Decentralized API Key Verification#

With decentralized API key verification, the central authority issues a signed token as an API key. Such tokens use public key cryptography to allow an API server to validate them without communicating with the central authority on every request. The signature is signed by the central authority using a private key. The corresponding public key is published and retrieved periodically by the API server. The public key verifies that the token was signed by the central authority, which means that the contents can be trusted. When the contents of the token are examined, they can provide other information about the requester or operation, including when the token expires, who created the token and more.

sequenceDiagram actor User as Richard participant RS as Todos API Server participant AS as Central Authority RS ->> AS : Retrieve Public Keys Note right of User : ... Time passes ... User ->> RS : Present API Key, Request Data RS ->> RS : Check Signature RS ->> RS : Check Data in Key RS ->> User : Return Todos Data

Validation using signed API keys.

The OAuth standards can be used to implement decentralized API key verification. Let’s map the words used above into OAuth terminology:

| Term used above | OAuth term | OAuth abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| client | client | n/a |

| central authority | authorization server | AS |

| API server | resource server | RS |

| API key | access token | AT |

For clarity, this post will continue to use the non-OAuth terms, such as API server.

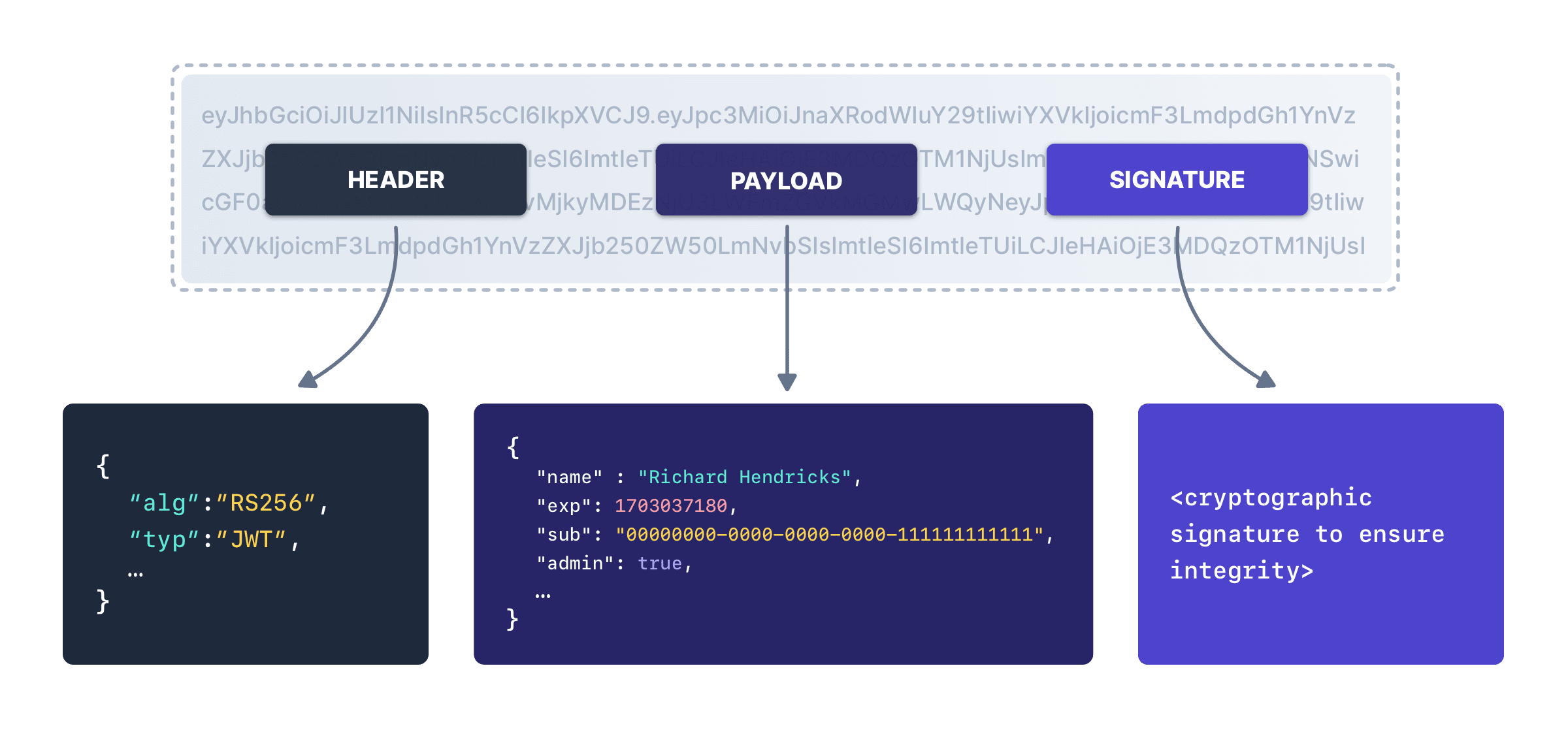

An API key in a decentralized system is often a JSON web token (JWT) which carries more information than a simple API key in a centralized system can.

A signed JWT has three components. A header with metadata, a payload with data, and a signature for integrity checking.

The payload can be trusted because of the signature. The existence of the signature means that the API server can verify that the contents of the API key were not changed after it was created by the central authority.

An API key which is a signed token can include data such as:

- the user identity

- who the API key is intended for

- who created the API key

- business specific information like the account level of the user

With the decentralized option, you have far less communication with the central authority. Because of the signature integrity guarantees, you can use the payload to reduce network calls and increase scalability. Additionally, systems can be more isolated as there isn’t the same single point of failure and can continue to operate for a time if the central authority is unavailable.

The flip side of this decentralization is that revocation of the API key is more complex.

Why Not Both? OAuth Introspection#

As mentioned above, OAuth supports decentralized API key verification. However, if you use introspection (RFC 7662), then you can use OAuth as a centralized API key verification system.

With introspection, every time the API server receives a request, it presents the central authority with the API key. The central authority returns a response indicating whether the API key was valid or invalid. The format of the response is defined by the RFC.

sequenceDiagram actor User as Richard participant RS as Todos API Server participant AS as Central Authority User ->> RS : Present API Key, Request Data RS ->> AS : API Key Valid? AS ->> RS : API Key is Valid, Here's Data About The API Key RS ->> RS : Perform Additional Validity Checks Against Returned Data RS ->> User : Return Todos Data

Validation using signed OAuth introspection.

A typical response looks like:

{

"active": true,

"client_id": "l238j323ds-23ij4",

"username": "richard",

"scope": "read write share",

"sub": "Z5O3upPC88QrAjx00dis",

"aud": "https://todo.piedpiper.com/api/todo",

"iss": "https://auth.piedpiper.com/",

"exp": 1419356238,

"iat": 1419350238,

"subLevel": "premium"

}However, when using OAuth introspection, make sure you understand what a valid response from the central authority indicates. The active attribute is the only required value.

From the specification, active is a:

[b]oolean indicator of whether or not the presented token is currently active. The specifics of a token’s “active” state will vary depending on the implementation of the authorization server and the information it keeps about its tokens…

With OAuth centralized API key verification, you can’t rely on the central authority for everything. You must check the data it returns for correctness as well.

First Party vs Third Party APIs#

Another API security consideration is whether you are protecting a first-party or third-party API. In the example above, the todos client, the API server and the central authority are all owned by Pied Piper.

But what if Pied Piper builds a platform to foster an ecosystem of todos based add-ons. If this takes off, there are additional services which will make users’ task management experience more enjoyable. Some examples of third-party todo based enhancements include:

- an LLM based service to summarize todos

- a reminder service to read todo due dates and text or email a user about upcoming tasks

- an analytics service to give a user monthly summaries of their accomplishments

- custom clients to add todos using an Apple Watch interface

While all these services could be built by Pied Piper, if they open up a platform and provide the right incentives, they can harness the creativity and energy of more developers than they could ever hope to hire.

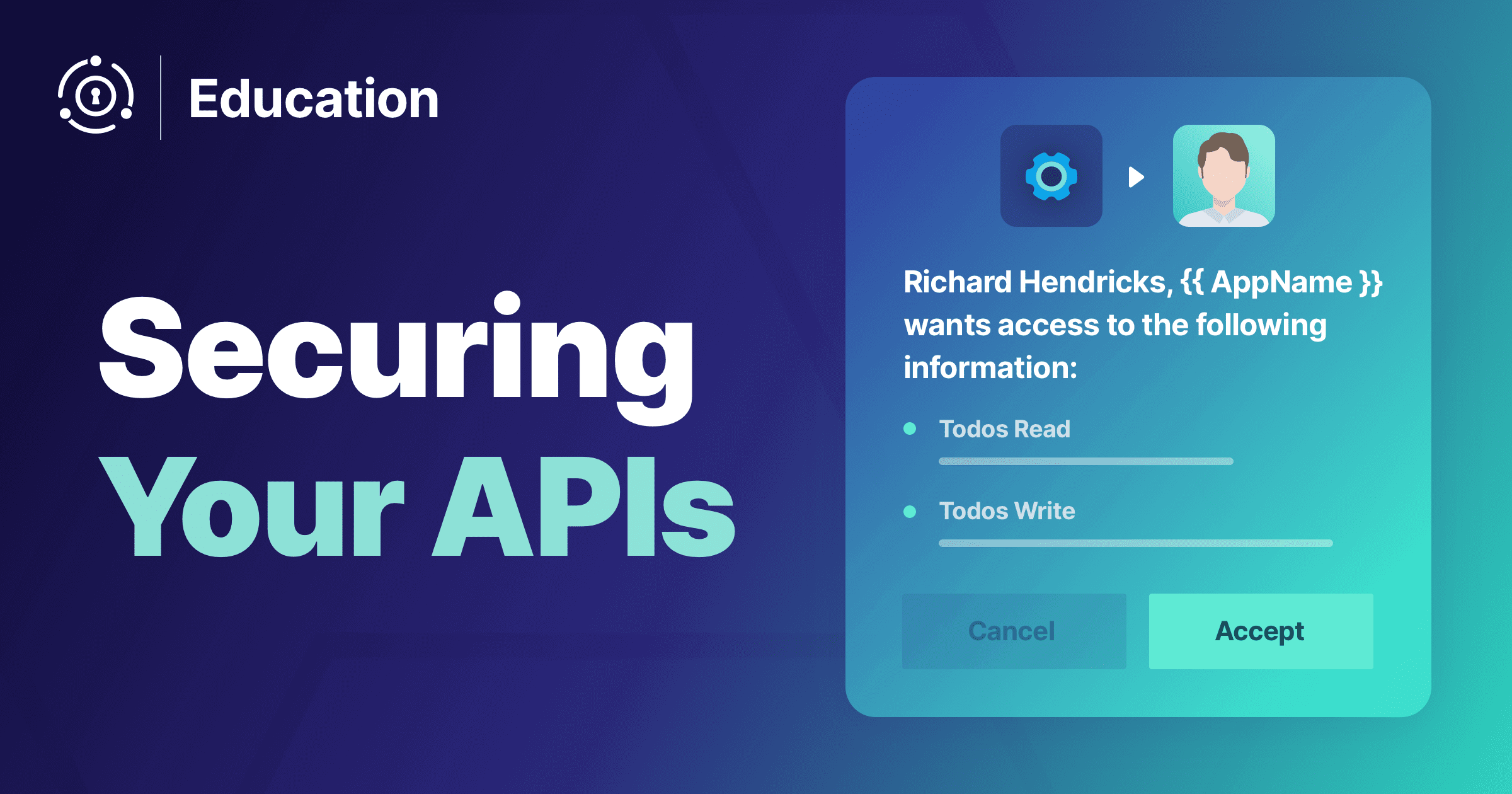

With such a platform in mind, Pied Piper needs to authenticate not just the API requester, but also control access in a more sophisticated way, based on what each service needs. For example, the Apple Watch client needs to be able to read and write todos, but the analytics service only needs to be able to read them.

Third-party API clients have specialized authentication requirements which are more complex than the first-party API clients that you learned about above.

Third Party API Authentication Requirements#

With third parties, define coarse grained permissions which control access to user data you hold. More importantly, you’ll need the client to ask permission for data access and the user to grant or withhold permission. That’s right, third-party clients aren’t granted access based on just what they are, but also on a user by user basis.

This permission request typically occurs when the user installs or authorizes access for a third-party solution.

In contrast, it doesn’t make sense for a first-party API to ask for a user’s permission to read or write certain data or operations because the first-party has access to everything.

The OAuth solution to the third-party problem is scopes. These strings define the permissions required and allow clients to ask users to grant them. Let’s dig into the standards based solution a bit more.

While the way the user grants the third-party application access to their data might vary, it could look like this:

- Richard visits a Pied Piper Todos Management System marketplace

- Richard installs a third-party app to summarize his todos with a LLM, called LLMSum

- Richard signs into LLMSum

- Richard is prompted to connect his LLMSum account to his Pied Piper account

- Richard starts connecting the accounts

- Richard is sent to the central authority server with a

readscope request - Richard is prompted to consent to the

readscope request - Richard consents

- Richard is sent back to LLSum which stores the API key which contains scope information as well as other data

- LLMSum makes a request with API key to the Pied Piper todos API server

- the todos API server validates the API key, including that the scopes included match the requested operation (a write request would fail)

- when validation passes, the todos API server returns todos data to LLMSum

- LLMSum does its LLM magic

- Richard is happy, see below

To follow the principle of least privilege and security best practices, the third-party application should ask for as limited a number of scopes as is needed to perform the operations.

Scope Validation#

Scope validation occurs in a few different places and times. Before a third party is granted access by the central authority to obtain API keys that it can then use to obtain user data, the scopes the third party requests are vetted to determine if they are appropriate. In the OAuth world, this vetting is part of client registration.

Next, when the third-party service requests access to a particular user’s data, as outlined with Richard above, the user should be prompted to grant consent.

This consent is critical for securing third-party application access. The presentation of the consent is controlled by the central authority, but should clearly lay out the ramifications of the data access to the end user. This is the user’s chance to disallow improper access to their data.

For instance, if the analytics tool asks for write access to the todos, the request should be clear enough that any normal user will prohibit it.

The central authority should also verify requested scopes. Since the scope request is under control of the third-party client, a malicious or buggy client could request disallowed values. If the central authority receives an initial scope request that was not granted to the third-party, the request is invalid and should not be processed.

Finally, if you are using scopes in a decentralized API key verification system, they should be validated by the API server to check that the scope in the API token matches the requested operation.

Designing Scopes#

Scope design is hard when first designing APIs, but even more painful to retrofit. Since third-party clients are building on top of the APIs you provide, updating or changing scopes will be a long, drawn out process.

Spend some time upfront thinking about what scopes make sense for your API. You want them to:

- be broad enough to cover a cohesive chunk of functionality

- be narrow enough to be useful to control access (avoid

superuserscopes) - be understandable to users

- have no overlap

- avoid being overbroad

Also, you don’t need to have scopes for every API endpoint. For example, there may be certain admin APIs which would only be usable by first-party applications. In that case, don’t write scope definitions for them. This avoids the possibility they’d ever be mistakenly granted to or requested by third-party applications.

One way to design your scopes is to break your APIs into discrete functionality and offer read and write permissions to each area. For the Pied Piper Todo Management System, scopes might be:

todo-read: the permission to read and list todostodo-write: the permission to create and update todos

As more API functionality is built, different read and write scopes can be added. It’s also easier to add new scopes than to remove them, so err on the side of minimalism. This is more of an art than a science.

Wrapping Up#

When you are exposing an API, you need to protect it.

You should think about whether to use a centralized API key verification system or decentralized verification. The centralized option requires constant communication between the consumers of API keys, the systems serving the API, and the central authority issuing API keys, all to ensure the validity of the keys.

On the other hand, a decentralized authentication system allows API key consumers to validate API keys on their own, increasing scalability but making revocation more complex.

You also may need to set up user based coarse grained permissions for third-party API applications when building a platform, using OAuth scopes or some other mechanism.

Protect your APIs like a pro. Schedule a demo to explore how FusionAuth secures API access with fine‑grained control and token management.