Security

Breached Password Detection

By Dan Moore

There are a large and growing number of compromised passwords available on the Internet. For example, Have I Been Pwned, one of the biggest public datasets, has over 10 billion compromised accounts. These include millions of accounts from popular services like MySpace, LiveJournal and Mathway. No fun!

Have I Been Pwned is one of the good guys. They are among the services sharing this data in an effort to help people. Users can find out if their credentials have been compromised by visiting that site, and people building and operating applications can access the data to help secure their systems.

There are other actors out there with, shall we say, less hospitable intentions, using breached datasets to gain unauthorized access to systems.

Of course, a great way to avoid unauthorized access is to secure your own systems. As part of that, encourage good security practices in your users, such as strong passwords and two factor authentication. Unfortunately, it’s common for people to reuse passwords across different applications and services. No matter how good your security is, if credentials are shared between systems, your application is as vulnerable as they are, should they suffer a data breach and leak passwords into the wild. Wikipedia has a list of hundreds of data breaches, including some from very large organizations.

What is breached password detection?

Breached password detection can help. This practice consists of the following:

- Finding lists of compromised passwords.

- Optionally building a system to download, process and store these datasets.

- Configuring or building a system to check passwords when authentication, registration and password events occur.

- Taking action when a leaked credential is found.

Lets cover each of these in turn, but first, let’s discuss some additional reasons why you might be interested in implementing this functionality.

Why implement breached password detection?

Beyond preventing unauthorized access to your systems, which is a substantial benefit desired by most, detecting when a user has compromised credentials has other benefits.

It is a service to your end users. Informing them that their account, and any other accounts that may share the same password, has been compromised is helpful. Depending on how you implement the notice, you may help them realize their danger. It’s easy to forget about an email or letter, but harder to ignore being unable to log in to an application you use.

Compromised password detection is also a protective measure that you, as an application developer or operator, can apply without requiring any user action; until a leaked or insecure password is found, of course. Following the principles of defense in depth, there are other user account security practices that you should encourage, such as two factor authentication. Most of these practices, however, require end user action.

Secure two factor authentication, for example, requires a relatively sophisticated user who can install and manage a TOTP application, as SMS is not a secure method for authentication, as has been known since at least 2016. SIMs can be swapped out by an attacker, as described in this 2020 paper (PDF):

We found that all five carriers [that they examined] used insecure authentication challenges that could be easily subverted by attackers. We also found that attackers generally only needed to target the most vulnerable authentication challenges, because the rest could be bypassed.

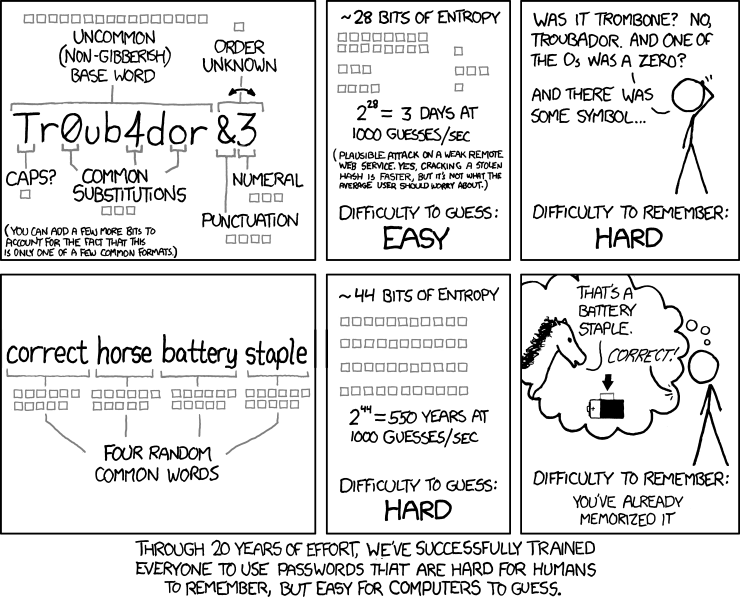

For users, especially when compared to the common practice of requiring a certain number of special characters or uppercase letters, checking for breached passwords is low impact. If it’s not delightful, it is at the least not frustrating. Enabling detection also expands the universe of acceptable passwords, which may now include long passphrases without any special characters.

What does NIST have to say about breached password detection?

In the same vein, NIST, an American government agency, recommends that auth systems should check user provided passwords against a variety of sources; a “memorized secret” is NIST-speak for password. From the “Digital Identity Guidelines” document:

When processing requests to establish and change memorized secrets, verifiers SHALL compare the prospective secrets against a list that contains values known to be commonly-used, expected, or compromised. For example, the list MAY include, but is not limited to:

- Passwords obtained from previous breach corpuses.

- Dictionary words.

- Repetitive or sequential characters (e.g.

aaaaaa,1234abcd).- Context-specific words, such as the name of the service, the username, and derivatives thereof.

If the chosen secret is found in the list, the CSP or verifier SHALL advise the subscriber that they need to select a different secret, SHALL provide the reason for rejection, and SHALL require the subscriber to choose a different value.

There are many other recommendations in the document and it’s worth reading. Further requirements include setting a minimum password length of at least 8 characters, if the user is choosing it. Another mandate is forcing a user to change their password if it has been compromised. In addition, these guidelines prohibit requiring certain characters in passwords:

Verifiers SHOULD NOT impose other composition rules (e.g., requiring mixtures of different character types or prohibiting consecutively repeated characters) for memorized secrets.

Why? Because doing so doesn’t work. From the NIST Guidelines FAQ:

These rules provide less benefit than might be expected because users tend to use predictable methods for satisfying these requirements when imposed (e.g., appending a ! to a memorized secret when required to use a special character). The frustration they often face may also cause them to focus on minimally satisfying the requirements rather than devising a memorable but complex secret.

Hopefully you’re convinced. Now, let’s return to our previous discussion of implementation details.

Finding compromised passwords

First, you need to find the plaintext passwords. There are lists on GitHub and elsewhere. Have I Been Pwned provides SHAs and counts and therefore may be of use in determining how commonly a password is used. There are other providers out there, such as DeHashed or GhostProject. There may be substantial overlap between these providers.

You can also include lists of common words and character sequences in your datasets. These may not be present in any public data breach, but are used often enough that they are easy for an attacker to guess, and so should be avoided. Feel free to augment your lists with any other dictionary lists you can put together.

Whatever you do, please ensure you include correcthorsebatterystaple (image courtesy of xkcd).

Make sure you are researching these providers and datasets on a regular schedule, since new breaches happen and new providers may appear. You’ll also want to comply with any licensing or other requirements the data providers have. Some providers offer these datasets for free, while others may charge or ask for a donation. Make sure you set aside budget for this.

When you have found these datasets, you’ll want to download, process, and store them.

Download and store the breached password datasets

Now that you’ve catalogued the common passwords and known compromised credentials lists, you can build a system to download and store these data sets. Then you’ll want to make them available to your authentication system.

This is a fairly standard data ingestion problem which has been solved in many contexts, so I won’t go into nitty gritty details on how to accomplish this. However, make sure you’re ingesting this data on a regular schedule. You’ll also want to expose this service to your application or applications, possibly using an internal REST API or data export.

If you build an internal API, secure it carefully. Since you’ll be shipping your users’ passwords to and from it, use TLS. You may want to consider additionally encrypting the payload so that, on the off chance that if there’s a TLS exploit or your certificate is hijacked, passwords sent to the service will still be secure. FusionAuth encrypts the password on the client side using a per-client shared secret and then sends the password payload over TLS for two layers of encryption.

An alternative

Some services, such as the aforementioned Have I Been Pwned, also offer a REST API themselves. Such third party APIs may fit your needs. Like any software system, in building breached password detection, you will need to make tradeoffs. It is certainly simpler to rely on a third party API to perform breached password checks. What you lose is:

- Control: You can no longer add your own suggested dictionaries or other customizations. It becomes more difficult to isolate your systems from the Internet.

- Performance: You’re now going over the Internet, which will almost certainly negatively affect response times. How much? It depends. You’ll need to test.

- Reliability: Integrating an outside service could affect users’ ability to authenticate. Plan for the external service to fail to return results in a timely manner and ensure that your authentication system handles it.

Test any third party API thoroughly to ensure that your application won’t be negatively affected by relying on it. Authentication is a critical part of any application. If it is degraded, then the user experience is degraded as well.

Of course, you gain something when you use a third party API, too. Benefits include quicker time to market, reduced cost, or a simpler overall solution with fewer moving pieces. Starting with an API integration, perhaps using a library such as these, may make sense. It’s better to use a third party integration than to perform no breached password detection at all. Later, you can build your own data ingestion system as your use increases or you need more control.

In any event, now you have a source of compromised credentials and a way to check to see if a password is in that set.

Configuring your authentication system to check for leaked passwords

Now you’ll need to hook into your user management service. Depending on what kind of auth system you have, the integration may be more or less difficult. However, you’ll want to check passwords at a couple of different times during the lifecycle of a user’s interactions with your systems:

- When they register or an account is created for them.

- When a user changes their password.

- When an administrative user changes a password for someone else.

- When a user logs in.

You should enable checks on the first three events to prevent known compromised credentials from entering your system. The registration or password change should fail, with a clear message, if the user provides a publicly known password. You will want to enforce this even when a customer service or administrative user is setting a password for another user.

Detect breaches even when the password isn’t changing

The last one deserves a bit of explanation. Suppose a user signs up on Example.com with a great password. Then they come to your site and sign up with the same great password. They continue to use your site for months, but forget about Example.com.

Then, Example.com is breached. They may send out a notice, but your user may not receive it or may not change their password. This study from 2020 (PDF) covers a small dataset, approximately 250 users over two years. It found that of the approximately 60 users who had accounts on breached domains, only 13% changed their password within three months of the breach announcement.

If you only check for compromise when the password is created at registration or modified by the end user, you’ll end up with users who have credentials that have been leaked by breaches external to your system after account creation. The Example.com breach affected your system through the vector of the reused password. Detect breached passwords whenever a user logs in.

What does a breached password detection look like?

The actual implementation of the password check depends on whether you are using a third party API or a data ingestion system. If the former, consult the third party docs.

If the latter, you have a list of plaintext leaked passwords and you have the plaintext password from the end user. Don’t store the user’s password unencrypted anywhere other than in RAM! At that point, do a lookup against your list of passwords. If the user’s credentials are present, then the password has been compromised.

Unfortunately, such datasets can only provide proof of hazard, not proof of safety. If the dataset doesn’t contain the password, then it may have been compromised, but simply is not available in your datasets.

Why not compare the hashed values?

There are a couple of reasons. First, if a data breach occurs and the passwords were properly encrypted and haven’t been reverse engineered to plain text, the passwords aren’t very useful to attackers.

Second, and more importantly, I’ll assume you are salting your passwords and hashing them in a computationally expensive way; if not, here’s some math reading to do. In this case, to see if that password matched any on the list, you’d have to salt and hash all of the records on the list. Assume you could do that at a rate of 10,000 records a second, and you had a leaked password list of 500 million strings. This would take you approximately 14 hours to generate all the hashes. Generating the hashes to compare would take too long to do interactively or in a batch fashion.

Taking action when the breached password is found

Alright, we’ve built this capability and now have found a user with a breached password. What do we need to do? The best choice depends on the level of harm unauthorized access could cause. In increasing order of end user impact, the user management service could:

- Update an internal system, but not notify the end user. This might be useful if you don’t protect any data, but rather use authentication to throttle access or for reporting. If you are gradually rolling breached password detection out and expect user pushback when they are required to take action, you may want to get a baseline for how many compromised credentials are in your system currently.

- Notify the user by sending them an email, or contacting them in some other fashion, to let them know about the compromised credential. I’d suggest politely asking them to change their password at that time.

- Force them to reset their password. Most user management systems have a way to expire a password, so you can tie directly into that.

- Lock the account and prohibit any use until the situation is rectified. This may include resetting the password or other steps such as investigating to confirm there was not any unauthorized access.

Consider the privilege level of the account with the breached password. If the user is an administrator, you may want to take different actions than you would if they are a normal user.

External integration

Depending on the breadth of your digital infrastructure, you may need to integrate with external systems when an account credential is compromised. Whether this happens in an entirely automated fashion or kicks off a manual process depends, again, on your security posture. Ensure the authentication system you are integrating with can fire off events notifying other interested systems.

You also may want to be able to run reports or other analytics to determine if there are any patterns to the compromised passwords, or simply to know how many of your users have been affected. These reports may be provided in the auth system. An alternative is to use or build an analytics system and have it subscribe to the published password breach events.

Performance

All security is a tradeoff; in this case, checking if password is breached is going to have an impact. The question is, how large is it? If you are looking up plaintext passwords in a database, the performance impact should be minimal. If there are network calls required, that may add some latency as well.

It also depends on how many registration, password change and login attempts occur over a given timeframe. Only you can test in a real-world scenario and determine the performance impact on your system. If you are concerned about performance, one way to increase it is to have the data close to your auth system to minimize network delay.

Finally, consider the performance impacts of having to take your system down because there was substantial unauthorized access, because another system had a data breach and users didn’t have unique passwords. That doesn’t sound so fun to me.