Tokens

Building A Secure Signed JWT

By Dan Moore

JSON Web Tokens (JWTs)_ get a lot of hate online for being insecure. Tom Ptacek, founder of Latacora, a security consultancy, had this to say about JWTs in 2017:

So, as someone who does some work in crypto engineering, arguments about JWT being problematic only if implementations are “bungled” or developers are “incompetent” are sort of an obvious “tell” that the people behind those arguments aren’t really crypto people. In crypto, this debate is over.

I know a lot of crypto people who do not like JWT. I don’t know one who does.

Despite some negative sentiment, JWTs are a powerful and secure method of managing identity and authorization — they simply need to be used properly. They have other benefits too, they’re flexible, standardized, stateless, portable, easy to understand, and extendable. They also have libraries to help you generate and consume them in almost every programming language.

This article will help make sure your JWTs are unassailable. It’ll cover how you can securely integrate tokens into your systems by illustrating the most secure options.

However, every situation is different. You know your data and risk factors, so please learn these best practices and then apply them using judgement. A bank shouldn’t follow the same security practices as a ‘todo’ SaaS application; take your needs into account when implementing these recommendations.

One additional note regarding the security of JWTs is that they are similar in many respects to other signed data, such as SAML assertions. While JWTs are often stored in a wider range of locations than SAML tokens are, it is always recommended that you carefully protect any signed tokens.

Definitions#

- creator: the system which creates the JWTs. In the world of OAuth this is often called an Authorization Server or AS.

- consumer: a system which consumes a JWT. In the world of OAuth this is often called the Resource Server or RS. These consume a JWT to determine if they should allow access to a Protected Resource such as an API.

- client: a system which retrieves a token from the creator, holds it, and presents it to other systems like a consumer.

- claim: a piece of information asserted about the subject of the JWT. Some are standardized, others are application specific.

Out of scope#

This article will only be discussing signed JWTs. Signing of JSON data structures is standardized. There are also standards for encrypting JSON data but signed tokens are more common, so we’ll focus on them. Therefore, in this article the term JWT refers to signed tokens, not encrypted ones.

Security considerations#

When you are working with JWTs in any capacity, be aware of the footguns that are available to you (to, you know, let you shoot yourself in the foot).

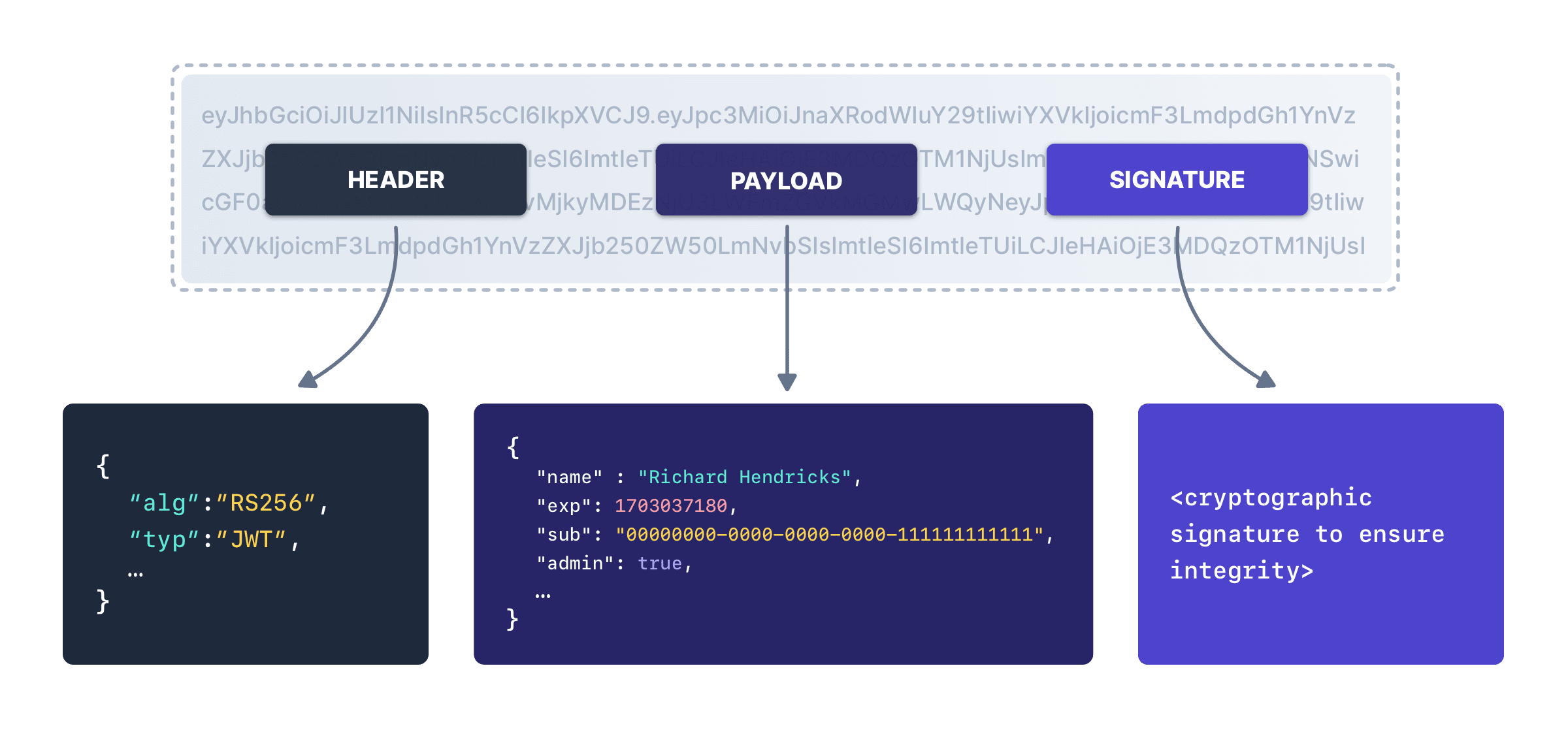

The first is that a signed JWT is like a postcard. Anyone who has access to it can read it. Though this may look illegible, it’s trivial to decode:

eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJpc3MiOiJmdXNpb25hdXRoLmlvIiwiZXhwIjoxNTkwNzA4Mzg1LCJhdWQiOiIyMzhkNDc5My03MGRlLTQxODMtOTcwNy00OGVkOGVjZDE5ZDkiLCJzdWIiOiIxOTAxNmI3My0zZmZhLTRiMjYtODBkOC1hYTkyODc3Mzg2NzciLCJuYW1lIjoiRGFuIE1vb3JlIiwicm9sZXMiOlsiUkVUUklFVkVfVE9ET1MiXX0.8QfosnY2ZledxWajJJqFPdEvrtQtP_Y3g5Kqk8bvHjoYou can decode it using any number of online tools, because it’s two base 64 encoded strings joined by periods, with a signature for integrity checking. The three parts of a signed JWT are a header specifying metadata, a payload containing claims and data, and the signature.

Keep any data that you wouldn’t want in the hands of someone else outside of your JWT. When you sign and send a token, or when you decode and receive it, you’re guaranteed the contents didn’t change. You’re not guaranteed the contents are unseen.

A corollary of that is that any information you do send should avoid unintentional data leakage. This would include information such as identifiers. If a JWT includes a value like 123 for an Id, that means anyone viewing it has a pretty good idea that there is an entity with the Id of 122. Use a GUID or random string for identifiers instead. Likewise, because tokens are not encrypted, use TLS for transmitting them.

Don’t send JWTs using an HTTP method that may be cached or logged. So don’t append the token to a GET request as a parameter. If you must send it in a GET request, use an HTTP header. You can also use other HTTP methods such as POST, which sends the JWT as a part of a request body. Sending the token value as part of a GET URL might result in the JWT being stored in a proxy’s memory or filesystem, a browser cache, or even in web server access logs.

If you are using OAuth, be careful with the Implicit grant, because if not implemented correctly, it can send the JWT (the access token) as a request parameter or fragment. For example, the Docusign esign REST API delivers the access token as a URL fragment. Oops.

Creating tokens#

When you are creating a JWT, use a library. Don’t implement this RFC yourself. There are lots of great libraries out there. Use one.

Set the typ claim of your JWT header to a known value. This prevents one kind of token from being confused with one of a different type.

Signature algorithms#

Choose the correct signing algorithm. You have two families of options, a symmetric algorithm like HMAC or an asymmetric choice like RSA or elliptic curve (ECC). The "none" algorithm, which doesn’t sign the JWT and allows anyone to generate a token with any payload they want, should not be used and any JWTs that use this signing algorithm (meaning they aren’t signed) should be rejected immediately.

There are two main factors in algorithm selection. The first is performance. A symmetric signing algorithm like HMAC is simply faster. Here are the benchmark results using the ruby-jwt library, which encoded and decoded a token 50,000 times:

hmac encode

4.620000 0.008000 4.628000 ( 4.653274)

hmac decode

6.100000 0.032000 6.132000 ( 6.152018)

rsa encode

42.052000 0.048000 42.100000 ( 42.216739)

rsa decode

6.644000 0.012000 6.656000 ( 6.665588)

ecc encode

11.444000 0.004000 11.448000 ( 11.464170)

ecc decode

12.728000 0.008000 12.736000 ( 12.751313)Don’t look at the absolute numbers, they’re going to change based on the programming language, what’s happening on the system during a benchmark run, and CPU horsepower. Instead, focus on the ratios. RSA encoding took approximately 9 times as long as HMAC encoding. ECC took almost two and a half times as long to encode and twice as long to decode. The code is available if you’d like to take a look. Symmetric signatures are faster than asymmetric options.

However, the shared secret required for options like HMAC has security implications. The token consumer can create a JWT indistinguishable from a token built by the creator, because both have access to the algorithm and the shared secret.

The second factor in choosing the correct signing algorithm is secret distribution. HMAC requires a shared secret to decode and encode the token. This means you need some method to provide the secret to both the creator and consumer of the JWT. If you control both parties and they live in a common environment, this is not typically a problem; you can add the secret to whatever secrets management solution you use and have both entities pull the secret from there. However, if you want outside entities to be able to verify your tokens, choose an asymmetric option. This might happen if the consumer is operated by a different department or business. The token creator can use the JWK specification to publish public keys, and then the consumer of the JWT can validate it using that key.

By using public/private key cryptography to sign the tokens, the issue of a shared secret is bypassed. Because of this, using an asymmetric option allows a creator to provide JWTs to token consumers that are not trusted. No system lacking the private key can generate a valid token.

If you have a choice between RSA and elliptic curve cryptography for a public/private key signing algorithm, choose elliptic curve cryptography, as it’s easier to configure correctly, more modern, has fewer attacks, and is faster. You might have to use RSA if other parties don’t support ECC.

Claims#

Make sure you set your claims appropriately. The JWT specification is clear:

The set of claims that a JWT must contain to be considered valid is context dependent and is outside the scope of this specification.

Therefore no claims are required by the RFC. But to maximize security, the following registered claims should be part of your token creation:

issidentifies the issuer of the JWT. It doesn’t matter exactly what this string is as long as it is unique, doesn’t leak information about the internals of the issuer, and is known by the consumer.audidentifies the audience of the token. This can be a scalar or an array value, but in either case it should also be known by the consumer.nbfandexpclaims determine the time frame that the token is valid. Thenbfclaim can be useful if you are issuing a token for future use. Theexpclaim, a time beyond which the JWT is no longer valid, should always be set.

Revocation#

Because it is difficult to invalidate JWTs once issued—one of their benefits is that they are stateless, which means that their holders don’t need to reach out to any server to verify they are valid—you should keep their lifetime on the order of hours or minutes, rather than days or months. Short lifetimes mean that should a JWT be stolen, the stolen token will soon expire and no longer be accepted by the consumer.

But there are times, such as a data breach or a user logging out of your application, when you’ll want to revoke tokens, either across a system or on a more granular level. You have a few choices here. These are in order of how much effort implementation would require from the token consumer:

- Let tokens expire. No effort required here.

- Have the creator rotate the secret or private key. This invalidates all extant tokens.

- Use a ‘time window’ solution in combination with webhooks. Read more about this option and revoking JWTs in general.

Keys#

It’s important to use a long, random secret when you are using a symmetric algorithm. Don’t choose a key that is in use in any other system.

Longer keys or secrets are more secure, but take longer to generate signatures. To find the appropriate tradeoff, make sure you benchmark the performance. The JWK RFC does specify minimum lengths for the various algorithms.

The minimum secret length for HMAC:

A key of the same size as the hash output (for instance, 256 bits for “HS256”) or larger MUST be used with this algorithm.

The minimum key length for RSA:

A key of size 2048 bits or larger MUST be used with these algorithms.

The minimum key length for ECC is not specified in the RFC. Please consult the RFC for more specifics about other algorithms.

You should rotate your token signing keys regularly. Ideally you’d set this up in an automated fashion. Rotation renders all tokens signed with the old key invalid, so plan accordingly.

Holding tokens#

Clients request and hold tokens. A client can be a browser, a mobile phone or something else. A client receives a token from a token creator (sometimes through a proxy or a backend service that is usually part of your application). Clients are then responsible for two things:

- Passing the token on to any token consumers for authentication and authorization purposes, such as when a web application makes an HTTP request to a backend or API.

- Storing the token securely.

Clients should deliver the JWT to consumers over a secure connection, typically TLS version 1.2 or later.

The client must store the token securely as well. How to do that depends on what the client actually is. For a browser, you should avoid storing the JWT in localStorage or a JavaScript object. You should instead keep it in a cookie with the following flags:

Secureto ensure the cookie is only sent over TLS.HttpOnlyso that no rogue JavaScript can access the cookie.SameSitewith a value ofLaxorStrict. Either of these will ensure that the cookie is only sent to the domain it is associated with.

An alternative to a cookie with these flags would be using a web worker to store the token outside of the main JavaScript context.

For a mobile device, store the token in a secure location. For example, on an Android device, you’d want to store a JWT in internal storage with a restrictive access mode or in shared preferences. For an iOS device, storing the JWT in the keychain is the best option.

For other types of clients, use platform specific best practices for securing data at rest.

Here’s our recommendations on how to store tokens such as JWTs.

- Cookie: send the token down to the browser as a

Secure,HttpOnlycookie. If you don’t require cross-site cookie sharing, setSameSitetoStrict. Otherwise, setSameSitetoLax, which will share the cookies in certain situations. Learn more aboutSameSitesettings. - BFF/Server-side Session: store the token server side, in a session. This is also known as the “backend for frontend” or BFF pattern. The session is typically managed by a framework, and ideally adheres to the same cookie storage recommendations. Learn more about server-side sessions. Please consult your framework documentation around securing sessions and data in sessions.

- Native Secure Storage: when the client is a native mobile app, store the token in a secure storage area such as iOS Keychain or Android Keystore.

Here is a table of characteristics of recommended JWT storage options.

| Feature | Cookie | BFF/Server-side Session | Native Secure Storage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scalable client API requests | Yes | No | Yes |

| Revocation possible | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Revocation straightforward | No | Yes | No |

| Sticky sessions or session datastore required | No | Yes | No |

| Token sent on HTTP API requests automatically | Yes (you may need to tweak the credentials option) | No | No |

| Token can be presented to APIs on other domains | No | Yes (via server-side requests) | Yes |

| Works in a web browser | Yes | Yes | No |

The proper JWT storage choice is based on your threat modeling and how much risk a particular service can tolerate. You can also configure your JWTs to be short lived, which minimizes the amount of time a stolen JWT can be used.

If you need to lock down JWTs further, implement token sidejacking protection using cookies and a nonce. An alternative is DPoP, which uses sender-constrained (proof-of-possession) tokens to further minimize the risk of token theft and replay. To learn more about the Distributed Proof of Possession standard and FusionAuth’s support, see the DPoP documentation.

And here’s a longer, exhaustive list of possible storage options.

| Option | Strengths | Weaknesses | Security Considerations | Recommended | Supported By FusionAuth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Secure, HTTPOnly cookies | Tokens sent automatically when credentials option sent, widely supported | Won’t work if clients are not on same domain as the APIs, requires a browser, APIs must look for access token in cookie header, not in other places | Reduces attack surface by preventing JavaScript from accessing tokens, XSS resistant, but requires correct cookie configuration and same-domain policies | Yes | |

| Backend for frontend (BFF)/Sessions | Easy to revoke tokens, works with any client, can be combined with cookie approach to provide cross domain access if some APIs live on different domains | Additional server side component, less scalable because you are routing all API requests through the BFF, single point of failure for all API access | Minimizes token exposure by never sharing tokens with the client, but introduces a new critical infrastructure component that must be secured | Yes | |

| Native secure storage | OS-provided secure storage options like iOS Keychain or Android Keystore prevent token exfiltration | Platform-specific implementation | Prevents exfiltration by malicious apps, use TLS to prevent attacker-in-the-middle attacks | Yes | |

| Mutual-TLS (MTLS) | Tokens are bound to client, IETF standard | Not widely supported, requires every client to have an X.509 certificate | Offers strong token-binding security, but operational complexity and certificate management introduce significant overhead | (when available) | No; tracking issue |

| Distributed Proof of Possession (DPoP) | Tokens are bound to client, IETF standard | Requires per-request proof generation by the client and verification by APIs; clients must manage and protect a private key (non-extractable, rotation); APIs may need nonce/replay handling | Enhances token security by binding it to a client, but susceptible to implementation flaws and requires stringent key management | Yes, Please review our DPoP documentation for tradeoffs and integration guidance. | |

| Local Storage, IndexedDB | JavaScript can access token and send requests using Authorization or other expected header, supported by some frameworks (Amplify) | Tokens vulnerable to exfiltration by any JavaScript running on the page | Highly vulnerable to XSS attacks | Yes, but you have to write your own backend to deliver the token | |

| In Memory | Your code can access tokens but other code cannot | Tokens lost when the client reloads | Reduces persistence of tokens, limiting exposure | Yes, but you have to write your own backend to deliver the token | |

| Web workers | Browser APIs provide a layer of isolation between the web worker and the access token | All fetch calls must pass through web worker, have to use a library or write web worker integration code, malicious code may still be able to get data via the web worker, access token is removed when page is reloaded | Provides isolation for tokens, but risks persist with malicious code targeting the web worker or intercepting network traffic | Yes, but you have to write your own backend to deliver the token and front end JavaScript to store |

Consuming a JWT#

Tokens must be examined as carefully as they are crafted. When you are consuming a JWT, verify the JWT to ensure it was signed correctly, and validate and sanitize the claims. Just like with token creation, don’t roll your own implementation; use existing libraries.

Verify that the JWT signature matches the content. Any library should be able to do this, but ensure that the algorithm that the token was signed with, based on the header, is used to decode it. In addition, verify the kid value in the header; make sure the key Id matches the key you are using the validate the signature. It’s worth mentioning again here that any JWTs using the none algorithm should be rejected immediately.

Then you want to validate the claims are as expected. This includes any implementation specific registered claims set on creation, as well as the issuer (iss) and the audience (aud) claims. A consumer should know the issuer it expects, based on out of band information such as documentation. You should also ensure the JWT is meant for you.

Other claims matter too. Make sure the typ claim, in the header, is as expected. Check that the JWT is within its lifetime; that is before the exp value and after the nbf value, if present. If you’re concerned about clock skew, you can allow a few minutes of leeway.

If any of these claims fail to match expected values, the consumer should provide only minimal information to the client. Just as authentication servers should not reveal whether a failed login was due to an non-existent username or invalid password, you should return the same error message and status code, 403 for example, for any invalid token. This minimizes the information an attacker can learn by generating JWTs and sending them to you.

If you are going to use claims for further information processing, make sure you sanitize those values. For instance, if you are going to query a database based on a claim, use a parameterized query.

In conclusion#

JWTs are a flexible technology, and can be used in many ways. This article discussed a number of steps you can take, as either a creator, client or consumer of tokens, to ensure your JWTs are as secure as possible.