Tokens

Pros And Cons of JWTs

By Brian Pontarelli

This article provides an analysis of JWTs (JSON Web Tokens, pronounced “jot”) from how they are used to pros and cons of using JWTs in your application.

JWTs are becoming more and more ubiquitous. Customer identity and access management (CIAM) providers everywhere are pushing JWTs as the silver bullet for everything. JWTs are pretty cool, but let’s talk about some of the downsides of JWTs and other solutions you might consider.

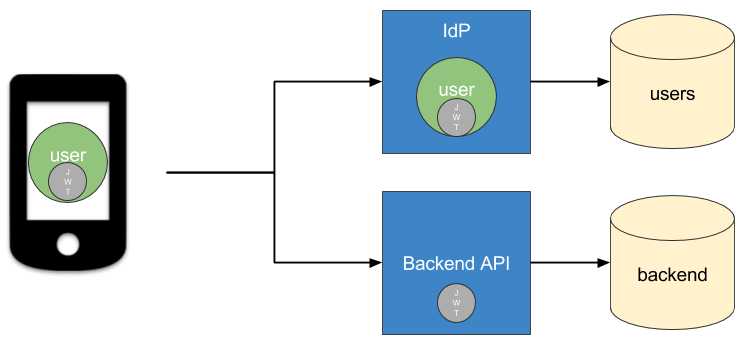

One way to describe JWTs is that they are portable units of identity. That means they contain identity information as JSON and can be passed around to services and applications. Any service or application can verify a JWT itself. The service/application receiving a JWT doesn’t need to ask the identity provider that generated the JWT if it is valid. Once a JWT is verified, the service or application can use the data inside it to take action on behalf of the user.

Here’s a diagram that illustrates how the identity provider creates a JWT and how a service can use the JWT without calling back to the identity provider: (yes that is a Palm Pilot in the diagram)

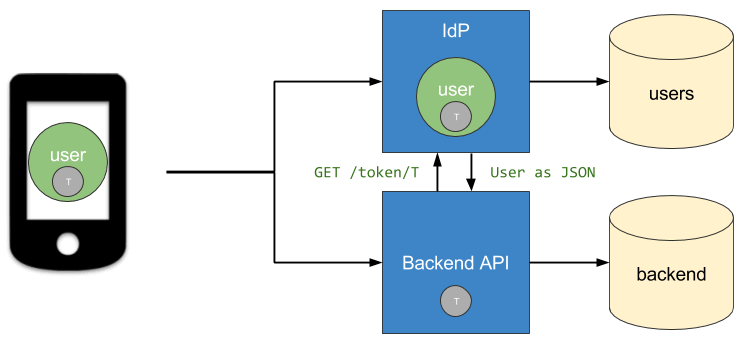

When you contrast this with an opaque token, you’ll see why so many developers are using JWTs. Opaque tokens are just a large string of characters that don’t contain any data. A token must be verified by asking the identity provider if it is still valid and returning the user data the service needs.

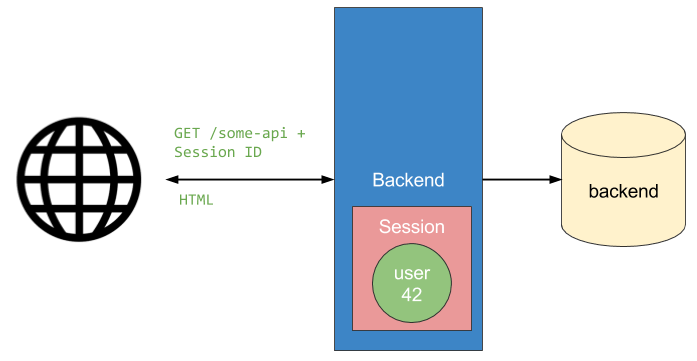

Here’s a diagram that illustrates how the identity provider is called to verify the opaque token and fetch the user data:

This method of verifying and exchanging tokens can be very “chatty” and it also requires a method of persisting and loading the tokens inside the identity provider. JWTs on the other hand don’t require any persistence or logic in the identity provider since they are portable.

There are a couple of things you should consider when deciding to use JWTs. Let’s look at a few of the main ones.

JWTs expire at specific intervals#

When a JWT is created it is given a specific expiration instant. The life of a JWT is definitive and it is recommended that it is somewhat small (think minutes not hours). If you have experience with traditional sessions, JWTs are quite different. Traditional sessions are always a specific duration from the last interaction with the user. This means that if the user clicks a button, their session is extended. If you think about most applications you use, this is pretty common. You are logged out of the application after a specific amount of inactivity. JWTs on the other hand, are not extended on user interaction. Instead, they are programmatically replaced by creating a new JWT for the user.

To solve this problem, most applications use refresh tokens. Refresh tokens are opaque tokens that are used to generate new JWTs. Refresh tokens also need to expire at some point, but they can be more flexible in this mechanism because they are persisted in the identity provider. This also makes them similar to the opaque tokens described above.

JWTs are signed#

Since JWTs are cryptographically signed, they require a cryptographic algorithm to verify. Cryptographic algorithms are purposefully designed to be slow. The slower the algorithm, the higher the complexity, and the less likely that the algorithm can be cracked using brute-force.

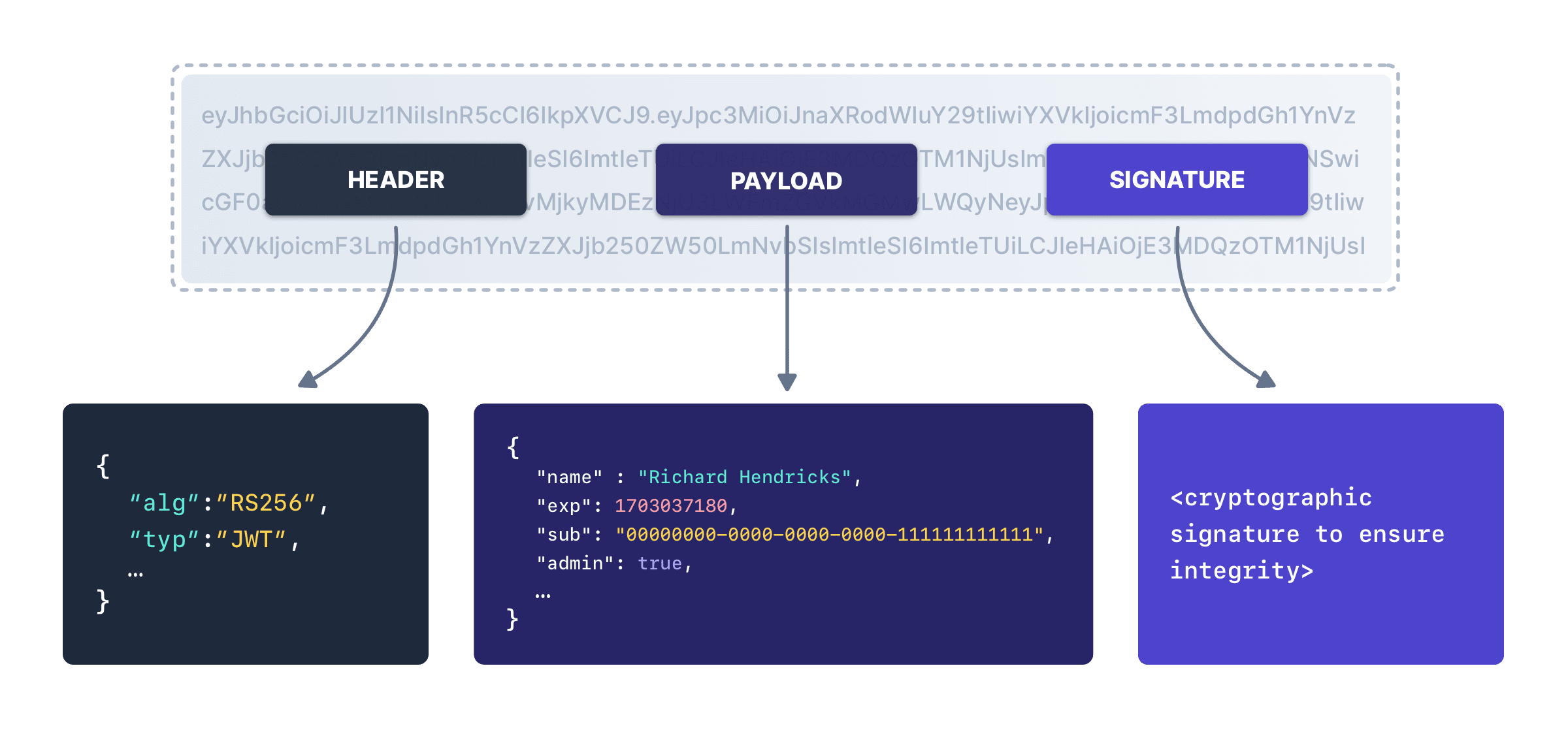

Every signed JWT contains a header, a body or payload, and a signature:

On a quad-core MacBook Pro, about 200 JWTs can be created and signed per second using RSA public-private key signing. This number drops dramatically on virtualized hardware like Amazon EC2s. HMAC signing is much faster but lacks the same flexibility and security characteristics. Specifically, if the identity provider uses HMAC to sign a JWT, then all services that want to verify the JWT must have the HMAC secret. This means that all the services can now create and sign JWTs as well. This makes the JWTs less portable (specifically to public services) and less secure.

To give you an idea of the performance characteristics of JWTs and the cryptographic algorithms used, we ran some tests on a quad-core MacBook. Here are some of the metrics and timings we recorded for JWTs:

| Metric | Timing |

|---|---|

| JSON Serialization + Base64 Encoding | 400,000/s |

| JSON Serialization + Base64 Encoding + HMAC Signing | 150,000/s |

| JSON Serialization + Base64 Encoding + RSA Signing | 200/s |

| Base64 Decoding + JSON Parsing | 400,000/s |

| Base64 Decoding + JSON Parsing + HMAC Verification | 130,000/s |

| Base64 Decoding + JSON Parsing + RSA Verification | 6,000/s |

JWTs aren’t easily revocable#

This means that a JWT could be valid even though the user’s account has been suspended or deleted. There are a couple of ways around this including the “refresh token revoke event” combined with a webhook. This solution is available in FusionAuth. You can check out the blog post I wrote on this topic here: Revoking JWTs.

JWTs have exploits#

This is more a matter of bad coding than flaws that are inherent to JWTs. The “none” algorithm and the “HMAC” hack are both well know exploits of JWTs. I won’t go into details about these exploits here, but if you search around a bit you can find many discussions of them.

Both of these exploits have simple fixes. Specifically, you should never allow JWTs that were created using the “none” algorithm. Also, you should not blindly load signing keys using the “kid” header in the JWT. Instead, you should validate that the key is indeed the correct key for the algorithm specified in the header.

Sessions as an Alternative#

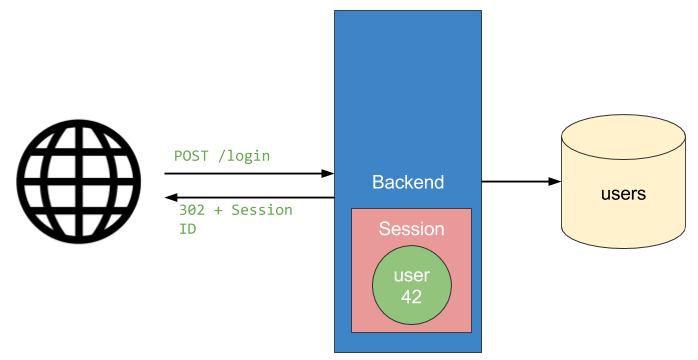

Instead of using JWTs or opaque tokens, you always have the option of using sessions. Sessions have been around for over two decades and are proven technology. Sessions generally work through the use of cookies and state that is stored on the server. The cookie contains a string of characters that is the session Id. The server contains a large Hash that keys off the session Id and stores arbitrary data.

When a user logs in, the user object is stored in the session and the server sends back a session cookie that contains the session Id. Each subsequent request to the server includes the session cookie. The server uses the session cookie to load the user object out of the session Hash. The user object is then used to identify the user making the request. Here are two diagrams that illustrate this concept:

Login#

Second request#

If you have a smaller application that uses a single backend, sessions work well. Once you start scaling or using microservices, sessions can be more challenging. Larger architectures require load-balancing and session pinning, where each client is pinned to the specific server where their session is stored. Session replication or a distributed cache might be needed to ensure fault tolerance or allow for zero-downtime upgrades. Even with this added complexity, sessions might still be a good option.

I hope this brief overview of JWTs and Sessions has been helpful in shedding some light on these technologies that are used to identity and manage users. Either of these solutions will work in nearly any application. The choice generally comes down to your needs and the languages and frameworks you are using.